- Vol. 03

- Chapter 04

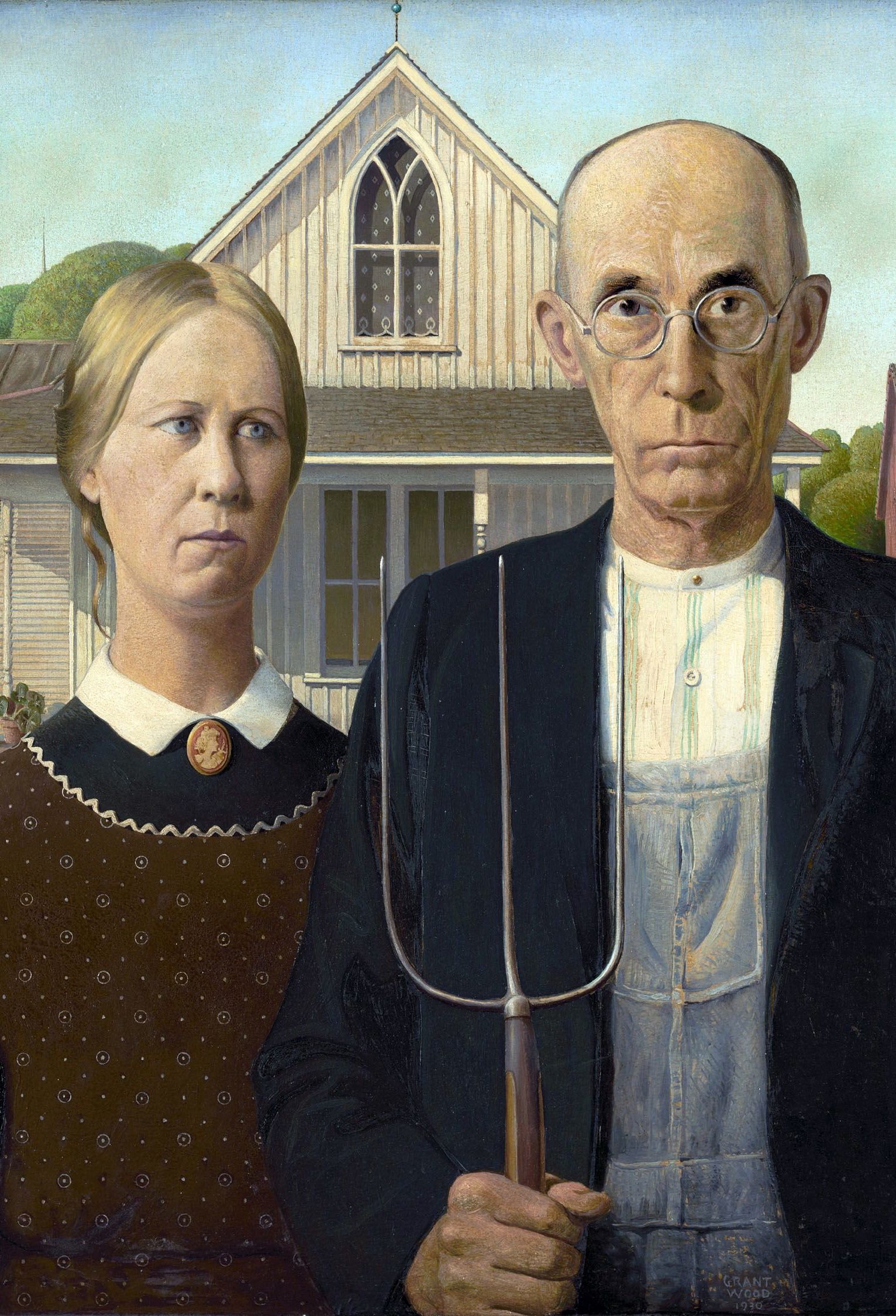

American Gothic

For God's sake, don't hand me

the pitchfork. I'll nestle instead

on the porch, by the geranium

that mimics those treetops ballooning

over the roof. The geranium,

that means, perhaps, incompetence

or friendship. Maybe both.

The geranium, the sweet scent

of which, I read somewhere,

resembles faintly the smell

of the ozone layer. Let me travel up

now, far from curtains and dentists,

through the simple stroke of a leaf―

a pioneer of the deficient,

piercing the clouds as I rise.

This Land

This land’s so full of spikes like you wouldn’t believe. Saul broke earth this spring early and found rows of them, growing like dragons’ teeth under the thin soil.

“Come out, Alice,” he yelled. “See this.”

Then it was a lot of questions for me. Had I happened to drop them, while I was out walking so much? I said, now where would I get a handful of spikes like these from? They were two inches long, of a thin bright metal, no sign of rust. Much heavier than they looked. The blunt ends plain and the sharp ends enough to poke through a potato’s eyes with no resistance. I know, I did it at the kitchen table, after Saul was done trying to get his answers from me. Potato with spikes through it. It looked like some kind of witchcraft, so I pulled the spike out and threw the tater quick on the fire.

He asked around the neighbours – each a half-hour drive away on the tractor – someone should know what the last leaseholders had been doing, if it was anything so strange. The neighbours said it was our land, our problem now. Saul tried to puzzle that one out a while.

“They seemed like good folks,” he told me, “but they went cold when I mentioned the spikes. They wouldn’t even take a look at them.”

“All of them the same way?” I asked.

Saul looked to heaven, “Yes, all of them, like I said.”

I was cleaning out the barn for the cattle coming. It was a fine place, no need of repair. But in the back there was a shelf, and on the shelf I found the spikes, raised up. Free standing like there was weights in the bottoms of each, but when I plucked one up, tried the same on the floor, I couldn’t find the balance. Read more >

Milk

I try to push through

to the pitcher of milk

that waits on the table

of the mourning house

but there is no

approaching the farmer;

his grip on the throat

of the pitchfork,

nor his solitary child;

a mute stockade

of unpainted fields

and deep buried bones.

Implement

To be born with a chin

so forlorn it’s a buttress against the neck a night without sleep an Emily Dickinson impression stubbornly held to; the kind that hopes neighbours will remark My! doesn’t she look a poetess

It was their compromise that the pitchfork

sit front in his hand, a whole fist around its shoulders with finger room for spare it was infidelity’s price

but how she loved its delicately

tripled tongue, the sharpness of that humour off-set by its cleft - into the wooden handle that it was upright and while directionless - aspirational - Read more >Gothic Telltale

Behind the agricultural frown are olden denim overalls. : The spectacled heron woos its paramour behind closed curtains.

Craning its long neck it remembers the sleeted wheat field. : Like a presaging raven portends the eventual sunset.

They age reluctantly. : Eyes open in voided obedience.

Faded and forked years are engrafted into the mona lisa background. : The whiteness of the American porch almost frightening.

Archaic Emoting

God bless the American Insurance system.Think: you could get some new glasses,

a thicker pitchfork that doesn't buckle

from the weight of a corncob.

A real man's pitchfork.

A pitchfork to skewer the heart

of every liberal sceptic in the country.

I could get a new dress, finally.

Or a new man. Hardship has made me

easy that way. Let’s burn it all down, honey.

Pretzl

I will believe the Lord is good.

I will believe the land is kind.

I do believe the fruit will fall

if not picked first and where it falls

must be controlled for fallen fruit will

surely rot and rotten fruit will sour the lawn.

My husband knows the hand of God

and God himself has made it known

that we should pick the ripening fruit

and love and keep the seeds we've sown,

we've sown. The precious seeds we've sown.

The cellar doors have sturdy locks

the windows open just enough.

Enough to let His spirit blow and clean

and keep the darkness holy, holy.

The shade that breathes in there.

Our seed that breathes in there.

Prongs of Three

He stares ahead,face wrinkled uniformly,

shirt mirroring the pattern of the prongs.

Garden pruned, woodwork washed

over the hauntings of gothic americana.

Hints of normality pushed aside,

the window shutters slammed shut. Woollen dress, so repressed

her life that could have been.

The prongs of three held steadfast amongst old time suburbia.

The air weighs heavy on his mind.

Where did it go so wrong?

Neurosity LXXXV: meditations on triangles in the early morning rain

dead leaves float free like emotionswith an equestrian discipline, cloistering

patterns of liquid hardness lightly aligned

with the borrowed warmth from your barefoot

contessa. the momentary solitude of mental

misfires hustle rational thought without furnishing

proper connecting dots in return. the way deer chat

on people’s lawns at dusk in your home town where

rivers flow in the wrong directions and smell like sulfur;

a town full of rawboned cows and crocked roads,

twenty churches and no bookstore to be found.

on your bed, you sprawl out restlessly thumbing

my words, allowing them to permeate your mind,

and decide that loneliness does not have to be absolute,

for now, even, just for now, but the physicality of words

is stale in comparison to the acute peppery-sweetness

of freshly chopped emerald basil. let me stay,

let me stay with the ease of watercolor

That’s Right, Ain’t It?

‘When I said, Defend the Faith, I didn mean what you did, you old fool. But you gone and done the worst thing a man can do, didn you? Jis because he didn agree with you. And you call it defendin the faith. Well it ain’t. And now you’s pretendin everthing’s all right, ain’t you? But I’s right beside you and I knows jis what you done. Even ifn you cleaned that pitchfork til it shines you ain’t gonna git away with nothin, cause I’s got you by the short and you-know-whats. Cause I knows your peculiarities.

‘You kin look all serious an sorrowful and like you’s no idea what I’s talking about, but you’s been and gone and done that awful thing and you’s goin to hell for it, donchu know it. So you stop starin out into the distance as if you’s all innocent as the day you’s born. You turn to me, your lawful wedded, and give me that damn’ pitchfork so’s I can do the necessary.

‘Tek them spectacles off, that’s right. Undo that collah stud, that’s right. Look me in the eyes. Straight on. Go on, stare at me, jis the way you’s been staring all day. Jis the way you musta stared when you done this god-awful thing, with that all-sorrowful, I-ain’t-done-nothin-but-what's-right look of yours. Well it ain’t gonna mek any diff’rence. Not now.

‘Watch me while I bend these prongs together, jis a bit. That’s right. You forgit I got some strength, didn you? All that log splittin and dough poundin. All that butcherin and tenderisn. There. Now, they’s jis the distance between your eyes, ain’t they? See that? Jis the distance. And if you’s worryin where that middle prong’s goin, there’s no need. I’s got the strength to plunge it between those sorrowfuls of yours. Easy.

‘Why’s you shakin? Divine Vengeance is acallin. You’s so busy cleaning them prongs you forgit to bury him proper. That’s right, ain’t it?’

The man who had no neighbours

‘No, I’m not a Hindoo,’ he said as he explained the picture on the bedroom wall and answered the question asked by the stranger who wanted to spend the night in his house, and then added, ‘and I am neither a farmer.’ Well, the house in the background too isn’t mine, he thought, but decided not to mention this. After all, if he started counting everything that wasn’t related to him, it would also mean the woman standing beside him, the pitch-fork, his clothes and even his stern and piercing look. Nothing was his and he knew this.

The stranger went on, ‘That weapon you’re holding is what the Hindoo Gods have in their hands. I can say this as I’ve seen plenty of pictures of these Gods.’ The stranger paused and then added, ‘And Goddesses.’

He remained silent for some time and then said, ‘Do I look like one those Gods in those pictures?’

‘The expression is quite like them,’ replied the stranger, ‘but I haven’t seen any of them as bald as you are.’

‘What’s the weapon called?’

‘It has a tri which is three and…’ the stranger paused as if squeezing the rest of the word out of some fold of his brain, ‘I think it was drool. No. it was school. Nah, can’t be that. Was something that rhymed with a fool.’

‘It is ok,’ he said, ‘it is enough to know that I resemble a Hindoo God.’

‘You also resemble someone who tried to molest my wife,’ began the stranger and he put his left foot on the rim of the bed on which he sat. The bed was next to the wall and he knew he couldn’t get off the other side. Read more >

Yokeland’s Best

“Babe, I want the bacon to be more crisp next time.”

“Yes dear.”

“And not just crisp around the edges. I want the entire strip of bacon to be uniformly crispy.”

“Yes, I’m sorry, of course ...”

“And the orange juice had too much sugar. If you can’t find oranges sweet enough to juice as is, added sugar isn’t the answer. Next time consider a different fruit. Grapefruits.”

“Certainly.”

“Pineapple maybe. You can add sugar to grapefruit or pineapple juice. But orange juice should be pure.”

“Then that’s what I’ll ...”

“Please, stop interrupting me. The pancakes were too dense. Did you beat the egg whites like I suggested?”

“I did, yes.”

“Well then you didn’t use enough baking powder.”

“I see.”

“Or the baking powder was past expiration. When was the last time you bought new baking powder?”

“Well, I’m not sure. I guess I’d have to ...”

“Just throw out the baking powder and pick up some fresh baking powder.” Read more >

Monsanto Ted Talk Plan

Develop, select, pay; register, analyze, define; survey, question, invite; winnow, weed, tier; reject, stalk, shade; budget, invite, manage, nag, deal; list, research, overestimate; borrow, beg, barter, pose: regionalize.

Engage, entice, excite; rope, follow, feel; group, tweet, skype; campaign, notify, email; prompt, invite, center: mythologize.

Register, check, brand; badge, bag, feel; stimulate, stream, flow, wow; hydrate, caffeinate, feed; enfold, squeeze, reap; network, interact, spam, engage. Curate. Satirize.

Take, get, upload; request, build, touch; keep, stay, engage; upload, spread, analyze; update, send, keep; stay, post, pay. Sleep, praise, litigate.

Land-bound Poseidon

This is where he makes his stand

Against any encroachment

From us, the outsiders

No point of entry

Trespassers beware

Trident in hand

He becomes a land-bound Poseidon

A tight-lipped sentry

Preparing to repel all invaders

Barricading his life behind

Closed curtains and closed doors

None shall pass

With his cameo consort at his side

As tight-lipped as he

They are proud in their defiance

Their rejection, of a world

In which they no longer fit

But here, it is we

Who are the strangers

And we are not welcome

Cameo

Sharp as metal eyesightthe iron fork is clean

as a collar-less shirt

denim dungarees

a starched pinafore

all those stern faces.

I bet if you pinched

their prayers, squashed

their long necks, tickled

the church spire that

the unsoiled couple

might contour a smile,

tis a human thing ain't it?

Pitchfork Justice.

I've told you before, they are not welcome here, Millicent.

They don't belong here with us, they are evil, foul creatures – not worthy of the name 'human.' They take liberties. They are other than us. They don't understand sensibility or sense.

Our lives by comparison, are pure, heartfelt, peaceful. There is no reason for us to change. We are innocent ones. Like finches nesting on the church – we are free. We are also free to plant grain and to sing songs of life and culture.

When you go to bed don't forget to pray for our souls, M. We are regular people, people who fear God and who are not afraid of His power.

Never forget – we are not like 'them.' We have no reason to feel guilty.

Your loving husband, P.

History of art

“What’s this?” you ask.

I take the sheet, two black and white photos, very cheaply printed. Are kids these days not entitled to a bit of colour?

“Oh, that’s American Gothic. And the other one looks like it’s by the same guy.”

“Gothic, like the ones in town?”

I smile. “No, not like them.”

I hope you won’t ask me to explain it properly. Once upon a time I would have been able to, would have been totally clued up. But that time has gone.

You don’t ask. You just give the paper a last scrutinise, brown wrinkled. Then you abandon it and run off. It falls to the floor like a feather.

I sit, overcome with a sudden heavy feeling, a kind of exhaustion but not a throw-your-hands-in-the-air one. A quiet one. My eyes slump shut, the paper blurring white and then disappearing into blackness.

Pictures jog across my vision. A Renoir-esque scene featuring a bunch of happy young things in a boat, the river green and the sky cloudless. A Mona Lisa, smiling but with that sideways, distant look, holding a scroll. Van Gogh fields with a swirly sky and a young woman wandering, attracted by the storm, by such blinding, flickering blue. Dali dream sequences, faces distorted, the world all the wrong colours and shapes and reality becoming further and further away and then – Guernica. The town bombed. Children screaming. Read more >

Aging in Place

It’s time to leave the man alone.

He’s getting old, his wife says.

He’s really slowing down.

He’s always been a man

occupied with one thing

or another.

No half way with him.

Now he finds harmless things

just to please the wife.

Three packs a day he smoked,

drank a pint every night, then

quit both for her.

Stopped chasing women too

when a widow nuts as him

called the wife.

All he does is weed

their garden beds and lawn

four seasons of the year

with the wife upstairs

at every window

keeping an eye on him.

Read more >

This is this and not that

Why people cannot see what this is and why they waste. It's a matter of liberty and the few things I have I have of my own sweat as it mixed there with my tools, the things I make and do with my ends. She says - when she sits down with me at the table after making food with her own hands - she keeps saying "we have what we have and they take it. I never wanted more than what was fair and I don't want to think about it. Not one bit."

As for me, I get up at the same time as ever and I do things careful and there it is. This is the thing, I got my end handled and why it's not working out? It's not on me. I'm not scared. I am full. Full up to my eyeballs. I don't want to make a deal. I don't want any more anything but I do want what's fair. It's got to stop. They have to stop. It's too much and I am full.

From One Man to Another

Yours is the face I recognise

Among a thousand fat-assed kings,

Drunk poets, wig-topped wankers and

I-know-you-did-last-year Christs.

I hold my broom to match your pose.

I have more hair than you. Har har.

No glasses, too. I'm fatter, though.

I wish my belly wouldn't grow.

These people never understand

How life is for the likes of us.

Their hands are good for dollars, dicks

And danishes but that is it.

We know the way of callouses,

And dreams that fade to darkness but

What did you dream of, buddy? Sir?

About how you had married her?

Stay Steady

The found her body by Forkfly Bridge, folded in two on the riverbank, a dismantled easel: limbs all over the place.

“She’s Bill Nightwalk’s girl,” the sheriff said, as he flipped her like a catfish, and she turned to face him: blue eyes clear as truth, hair draped round her neck like a lady’s choker, arms and legs marked by a mutter of bruising. A whisper that ended in silence.

“Who murdered her?” they cried that night: the man from-out-of-town in the idle suit, the fat bachelor drunk in the bar, the four-eyed kid in the steaming backyard, the greasy-haired mother by the too-hot kitchen stove, the bitter pin-thin lady at the Laundromat where Betty Nightwalk came to wash her clothes; A-line skirts, nylon blouses and cotton underwear. No nonsense. Betty was a bank clerk, a plain-faced girl, Bill and Annie Nightwalk’s only child.

Sheriff was the one to tell the family. Travelled to a dirt sprung farm, twenty miles from town. A journey so dry his tongue forgot to speak. Said words like a shot dog, a burnt house, a revolution:

“Betty’s dead.”

When he left, Bill took his pitchfork. He walked out of his house into a silence that swallowed the horizon, ate everything that had ever come before.

“Stay steady,” Annie said, “stay steady.”

“Beautiful Day, Sheriff!”

Ma couldn't help but nervously glance in the direction of the police cruiser pulling up the driveway.

Pa, on the other hand, stood stoic, steely eyed, and unflinching.

Ma worried they might have come with a warrant in hand.

Pa knew there was no way in hell he was going to allow those prying swine in HIS house, warrant or no warrant.

Inside their quaint, unassuming, farm house, the pile of bodies was still warm.

Back to back draughts and the two years of failed crops that accompanied them, mixed with the possibility of losing the farm that had been in their family for three generations. This had taken its toll on the two.

Pa had concocted a country-bumpkin conspiracy theory - he blamed the continual bad luck on the farmhands that showed up looking for work.

Ma and Pa were kind enough to give the guys a job when they appeared at their door after hoping off a freight train, but their tempers slowly boiled over as task after task turned into disaster.

Everything these guys touched turned to shit.

Pa began to think that the hobos were sent there by the bank to ensure they lost the farm.

Earlier in the day, Jimbo, the worthless worker/hired saboteur, ran the tractor into a culvert out in the field, rendering it useless. Pa had had enough.

Read more >

My Name is Dominika

If my icy stare startles your pitiful glare,

it's because of my empty living tomb -

My internal eternal gloom.

Let my lily-white complexion not divert

your eyes from my shameful family

connection – As his pursed determined

lips harden with each painful grip.

If my Siberian glinting orbs conjure up

tales of icy warmongering wars, then

drown in my lifeless fading frown -

As we guard this forlorn beastly town.

Don't be fooled by the pristine homely

ordinary facade, rather try to hear my

beaten beating bleating bleeding heart -

For my traditional pristine pressed dress

hides his painful camouflaged cursed

carnivorous caress – Each daily chore

ends with his vodka vomiting lustful

roar, this beast whose once saintly

heart is no more.

Read more >

American Gothic

Everything points to heaven,roof finial and ridge tiles,

arched window centred

on the clapboard house’s face,

porch pillars, modestly turned,

the woman’s hair, pinned

to make a steeple of her brow,

twin furrows above her nose,

ric rac binding her apron’s neck,

peak after peak after peak,

the pitchfork’s three prongs

in the lofty man’s firm grip.

The peep holes of his spectacles.

The black holes of his eyes.

The Upstair Neighbors

The daddy must be gnawing at the bones

of the mommy who coos, coos and coos

over the crying baby who makes a boo-boo, like all nocturnal families

do, oh they do, don't they, they do

the clunkity-clunk, the yakity-yak,

and the bibbidi-bobbidi-boo,

the happy rigadoon and a mouse at two

in the half-moon bedroom. I'm running out of

sleeping capsules, my tricolored silencio!

Red, white and bright starry blue. Saviors of America.

I mean, insomnia. No, really, I do

mean my nebulous wakefulness

at half past two.

Tell me what I should do, do, do

to stop my roof from – boom! boom! -

falling down. The woeful spinster clomps, clomps, clomps

clomps down on my papery skull. Why wouldn't she take off

her wooden shoes? Is she masking the echoes

of the owls' raucous hoots?

Up, up, up

into the reddening sky

I see them go.

They are all in cahoots!

A Garden of Beauty

Hank took his pitchfork and turned the soil. Insects and pebbles came to the surface while flies buzzed in his face.

“Will you remove those spectacles; you’re going to knock them clear off your face,” Hank’s wife Mary said from the front porch.

“Do I tell you how to cook? Go back inside and take that cameo off your blouse. You shouldn’t be wearing that in the house. I gave that to you to wear on special occasions.” He wiped the sweat from his face and sighed.

“Like we ever have any special occasions. It might as well sit in the box then.”

“Oh, go cook some dinner and leave me alone so I can tend to the garden. I do this for you, you know. I could have one of the neighbor’s sons do this instead of me breaking my back.” He touched his lower side and grunted.

“Yeah, like you’d pay someone to do gardening. That’s a laugh.” Mary tapped her knee and chortled.

“Don’t you have to cook dinner? Go inside and make stew or some other horrible dish that makes my stomach churn.”

“Keep it up and you’ll be eating outside with the cows tonight.” Mary slammed the door behind her.

Hank shook his head and continued with his work. After he finished with the soil, he pulled some weeds and planted a few yellow marigolds and pink begonias. His back ached, his knees throbbed and he was thirsty, but he stood tall in his blue trousers, filthy with dirt, and admired his small garden of flowers. He hoped Mary would appreciate it.

Read more >

A Modern Interview

"Are those glasses real?""What do you mean, 'real'?"

"You know, like, are they lenses?"

"Yes."

"..."

"Why wouldn't they be?"

"Because other people wear them without lenses."

"Do they?"

"Are they Dior?"

"No."

"Where did you get them from?"

"The thrift store."

"Really? Cool! Where's that?"

"Not really, I got them from Hank's Opticians."

"Oh. I like your dressing gown. It's very 'now'."

"It's a jacket."

"I see. Sorry. I can't see below your waist."

"Probably a good thing."

"What's that?"

"A pitchfork."

"Oh cute! Do you work on the city farm? I heard they do a great vegan breakfast."

"No, I have my own small holding."

"Like an allotment? That's so sweet. I've always wanted one of those. I like your dungarees."

"Thanks. I have seven pairs of these."

"Are they different colours?"

"No."

Read more >

The Guardians

Hardware store's clean out of fiery swords so my good old fork will have to do to guard, at God's behest, our garden gate from sinners and all uninvited guests. (It also makes a handy-dandy tool for opening a can of worms).

It falls to her, meanwhile, to bake the fruits of all these labours into pies according to the family recipe. Perfect prizewinners every time, they scream when she cuts them.

Trinity

We were born and brought up on this land. Our roots have been here for always. Back and back – our tree grew, inked in the front of the family bible. The book got swept away in the great flood, along with Grandpa and half our steers, I can remember it clearly.

We married young.

Seasons and years turned by, births and deaths, the sun always rose again. Crops grew, crops failed; one step sideways, one step back. With the clash of metal on stone, we dug our tears and our seed into the ground.

Pain and joy – the earth took all, twisting and queering our efforts.

Perhaps we might have migrated, but our roots were deep and entwined and we had been there too long. With no stone to step towards, we endured.

We became worn.

Sweat and tears grooved our faces. We weathered. Rain and sun bleached out our clothes and skin, and the wind blew the very fat from our bones.

Our marriage is a pitchfork, the middle tine stabbed into the dust so far, that we twist and turn in the earth’s breath. Together, we married the land – an unequal trinity, until the end.

Haul

They said he had crazy eyes, I didn’t

stand a chance at normalcy

but the gothic veneration of the air

that circled his head

the aura over the unnatural

that he exuded control

there was something about him;

his eyes didn’t comfort me like a lover –

they stirred my threshold of stability –

I could wear my prudence right up

to my neck and clench my chest

in corsets from alarm

his superficial glance at my face

would set off;

fantasies of his deft, warm fingers

around my restrained neck

I’d wonder how true his arms were

to the muscle of pitching and tossing;

wearing his heirloom medallion

on my collar like a nun from a harem,

Read more >

American Gothic

Holding the morning on the prong of a pitchfork

isn't as easy as it looks. That sudden spring

throwing its weight around, these shadows

of house on the lawn like a broken church.

I know no art but the rake, unearthing straw

by the barn, a festering gold buried under old rain.

God help me, I find my life there, flashes

of the woman I once hand fed raspberries, shrouded

by age. Bun the colour of sackcloth, she approaches,

all wife, whatever she wanted buttoned to her throat.

She sidesteps nibs of daffodils like painter's brushes

wrapped in brown paper, and simply watches me

compost. This man with a rake, dragging

his shadow closer again and again on Groundhog Day.

Playing Games

They don't always hold so still,

only when someone looks their way.

Close your eyes and listen

to the pinch of her fingers

on his chin, how his lips

crack and twist like barley sugar.

The handle thumps her foot, chipping

sequins from her thrift store sneakers,

and if you look again you'll see

tears pooled in the corners of her eyes,

how he presses on the handle,

how she can't quite stop her trembling chin.

O Master, you shall pay!

It’s such an odd thing to lose

Time has come to give Master some blues.

How dare he put the blame on me?

So easily he asked me to be on my knee.

How he forgot the service of all these years?

He made me cry and gave only tears.

How he yelled before his clan the other day?

I promise you dear, for what he did, I’ll make him pay!

The way you served everyone in the house

Be it his mistresses or his spouse.

The line was crossed when he tore away your blouse

I still can’t believe he’s such a rude louse!

I begged him, I pleaded him, I even prayed

He promised for mercy and then betrayed

One day his body will be decayed

I’ll destroy him and the message shall be conveyed.

Using my instrument, we’ll kill him first

For that’s the only way, to quench away my thirst.

We’ll bury him down and then get dispersed

Nobody shall know of our act done unrehearsed!

The New Gothic: Marriage

We resistthe pull of time;

resist being

too weak a word.

How easily

we fell in

love; as easy

as hitting

the floor. Dust

crawling by—

shed skin

reanimating

itself—across

exposed wood.

There is so much

work waiting

to be done.

We’ll get to it.

Just keep staring

straight ahead.

We Picked a Bad Time

She has come from the kitchen

(still in her pinafore)

to join him. He has pulled on

his coat, dignity enough

to meet whoever we might be:

company or intruders.

His eyes are fixed on me; I

shift position awkwardly

to ease the discomfort

of his piercing, rock-sharp

stare, but I cannot shift

enough to shake them

loose. In the periphery

of my vision, I escape

to wonder at the perfection

of the tiny stitches, each

precisely the same length,

that fix the strip of white

rickrack to the top of her

brown pinafore so that it

lies flat against the somber

black of her everyday-best

Read more >

Sweet Home Chicago

Jayden’s slumped on the bench staring at his feet when Mrs Jacobsen sits down beside him.

‘So, what do you think?’ she asks him.

She means about the painting. Jayden’s slumped in front of ‘American Gothic’ but he can’t make eye contact with it and I can’t say I blame him.

You know the painting, right? The guy with the pitchfork? There’s some serious tight-lipped weirdness going on in that painting, especially when you see it up close. It’s why Jayden can’t look at it. Neither can I.

Anyway, he says nothing to Mrs Jacobsen, just shrugs and makes a little grunting sound that’s barely audible.

The sort of answer the guy in the painting might give if you were to ask him how things were going.

‘Good harvest this year, McKeeby?’

‘Muh.’

Mrs Jacobsen pats Jayden on the shoulder.

‘Well, just write down whatever comes into your head. Go with your gut and see what you come up with.’

Jayden nods and looks up at the painting, but I can tell he’s looking past it at the wall.

When Mrs Jacobsen leaves I go over and sit beside him.

Read more >

Farmers Almanac

House like a church. Dour. Ribbed. Centered between these two corn-fed Iowans. Man in overalls and his Sunday best. A hard man. Look at his mouth. Woman in apron and cameo. Look at her shadowed eyes. Imagine the bedroom. The bed. Does she wash the sheets often? Maybe. Notice the one escaping tendril from her bun. Notice the barn. Barely there. What does that say? Ask yourself, whose hand is on the pitchfork?On the Psychology of Quantum Mechanics

So many sighs, those pitchfork smiles

from “farmers of physics,”

there’s much uncertainty about these mechanics,

though someone said, God doesn’t throw dice!

However, I say that the whole prospect

of mining the field is suspect, a huge gamble.

Like some people I know, every particle

of substance suffers schizophrenia.

One moment it’s a wave, the next, a particle

bouncing off walls. I didn’t know that

studying bipolars might make me manic. Still

there’s nothing gigantic about quantum leaps,

just discreteness of encounters.

American Gothic

They were made of stern stuff, the Flemish masters. No smiling in those portraits. Immortality was a serious thing. Everything was painted in the light of eternity, even lemons on a plate and still life studies of bread and cheese.

Grant Wood saw the rolling fields of the heartland, black dirt rich from retreating glaciers produced such plenty, too, before fields dried up in the dust bowl, and tears fell on bank foreclosures.

In the American galleries in the Art Institute of Chicago, you will find American Gothic, by Grant Wood. The man and woman stand together in that painting on the wall. You have seen it before. It is so familiar, you can't remember when you saw it for the first time. You have seen it, but not really seen it. It looks like an old painting, from the 1800s maybe, but it was painted in 1930. It is painted in the light of eternity and the Great Depression. There is a seriousness. These people stand their ground.

Today, people come to the museum from all over the world. "Where's the farmer?" they ask. It is one of the most frequently asked questions. They want to see the famous painting by Grant Wood. Everyone sees something different. They want to know what it means.

In the gift shop, there are many versions of this image – mugs and postcards, note cards, prints and posters. There are books on the art of Grant Good. Maybe the visitor will buy a postcard, or a magnet, a memento of this place, their visit to the city, gleaming by the lake. They will take the magnet home to Saint Louis or Paris. They will put it on their refrigerator, where it will secure a shopping list or a child's drawing – a house, and a family, with a cat and a dog.

Bloody Where the War Is Waged

It’s OK to scowl

when things ain’t right

with the world

No fake cheese

for the camera

in the cornfields

I’ve got a weapon

you’ve got a weapon

we’ve all got weapons

so let’s go to war

It’s the only rational

proclamation

for a Puritan

dressed up on Sunday

in a tight-buttoned

sun-splashed hallelujah

parted straight

down the middle

of a blood red sea

ready to spill...

everywhere

Abe the Storyteller

Of course, it would have to be his idea; he liked knowing what others could only guess at. Abraham was like that; he liked to play games.

Just the other day, he asked Mary Miller over; such a plain, dowdy and simple creature with mud-brown hair and cloud-grey eyes. Recently turned thirty and still a spinster.

I was particularly annoyed with Abe showing Mary our vegetable patch like that, talking about it as though it had won first prize at the county fair. There weren’t many vegetables to show, just rows of shoots pushing their leafy heads through the recently ploughed earth.

Of course I knew the reason for the slow growth of our vegetable patch. (Thankfully Abe kept this little nugget of knowledge to himself.)

I studied Mary Miller’s expression from the kitchen window; she wasn’t sure what Abe was showing her. Bless her little cotton socks. She nodded politely and listened to the great storyteller feeding her lie upon lie upon lie.

After she left, Abe came inside and poured himself a glass of cold lemonade.

‘So, what did you say to her?’

He didn’t look at me. Instead he took a long gulp of lemonade and wiped his mouth on the back of his hand.

‘Nothing important Lizzie, so there’s no need to worry.’

Read more >

Refused portrait sitting

In tradition there's safekeeping

in lordly fear the meek may yet thrive.

Fasting for austerity, neatness in all

manner of goodly godliness.

Engage ye must in pitched battle with

the wicked's work... purest living against infidels

has need of ready buttresses. Shoring up all

walls with faith, persistently.

One prong for every three wrong

delivered with forked-tongue.

There is no time, leisurely, to smile sitting

- even less for trivialities.

The land inherits all souls after harvest.

Our Home

We cleaned the place before the cleaners came

Not wanting them to sense the slob

Our hearts had became

Our home lingers over us,

Like a spaceship that owns us.

We stand under its spell as ornaments

Needing a good dusting

We watch quiz shows in the day

And the news each night

Simultaneously keeping us fearful

Of outsiders winning our jackpots

Or raping the kids we forgot to make

We’re the fork in the road

That scares destiny away

‘Leave us alone,’ you scream

To the wind blowing the scarecrow’s hair

Our minds are crippled by routine

If anything alien comes between

We will make sure to vomit it clean

Remember, without hope there’s only fear

And without humans, guns remain aimless

Anamosa, IA

When I was seven the

neighbors across the street

scared me. They

kept to themselves most

of the

time. They

had no kids,

no nearby kin,

no car,

no criminal records,

no

nothing.

He would

sit

on the porch, rocking

back and

forth

in his chair as his

bones cooked

in the sun. She would

stare from

behind intricate stained-

glass windows, gritting her

shark teeth to tiny

nubs against the

sill.

Read more >

Her Comic Valentine

She's on her knees, hands bunched beneath chin, eyes shut. Muttering.

He can't drag his gaze from the fields outside, rows of brittle brown. Don't matter what she asks for, crops are charred.

He takes a stick to Samuel, beating like the sun. Says he'll knock sense into the lad, but all she sees are ticks on ticks, stammers and fits. And falling down. And still he blames her God.

Next year, only the harvest spills across his hands; their girls nudge and pinch through grace, on a rare day spared of chores.

She consents to stand beside him, between meals, whilst a likeness is sketched.

The artist frowns, something's off: bring a pitchfork, he says.

Cumin of Agen

'Glanhd don't no messin' no - he tells er stright in thee cumin of Agen,' Frabd said, all beemso and pleesed. Lil shiften and sqkern, the cait's needles were duggin in right and true into her leig.

'Missy doen't do thit, thows sharps wuld maken the waater comes in at bathin' tyme.' Lil put Missy downe inter box-box but she'en cud never stay her place. Frabd pointed duwn at Lily's beluw spacen.

'Dos it hurtend? I member myne, fair red spurtin' hadta catched it in a pan-pan - Ma luked at me lik shesa gonie cooker-it up for dins!' Frabd chucked and squyer louder, Lil red-dener n cheiks. Dullen acke groins and a spotten knick-knucks wasna new, but shein ne'er tolden Glanhd or Planhd efore. Frabhd clappen and chucked seeing Glanhd and Planhd druking the paff towards they twoen. Lil fayre winken and fained at seein the three-sharpen stedl in Planhd's pinks and the blanken bare-ace of Glanhd.

A DARKER WOOD

She glares her distaste and anger

Into the back of his right pinna:

Emotions of the model

Encroaching on the character.

She doesn’t like dentists.

Artist slouches behind the easel:

Canvas concealing his grinning face

As wry he reproduces

Each crease of her disapproval.

Adds mother-in-law’s tongue

To porch of Carpenter Gothic:

Borrowed pretentiousness he mirrors –

Pitchfork in uncalloused hands;

Potted Med and African plants;

Starched suit on dungarees…

On beaverboard.

They are gone far

they are gone far

out of this country

out of this county

our children are gone

to reach the metropolis

they left their mother

to gain a new patriotism

they left their father

they are gone far

to forgot about farms

to find a new warm house

no more wheat

no more straw

there is no sweat

on their foreheads

there are no scars

on their hands

the ground is left

and so the wound

and the ancient traditions

but we will wait

we will stay here

working with hands

sweating with foreheads

Read more >

Mourning Ms Pyrex

Let's give Ms Pyrex

something to remember

something to take home with

as she journey peacefully to yonder

Let's give her something

to look at and say

I was here

The grave indeed is a fine place to be

and I wish Mr Pyrex

had had enough money to call in a gold hearse

but drought visited his farm

and his wealth travelled with the wind

Let's give Ms Pyrex something

to remind her that her struggle to keep the house in order

was not in vain

as she goes straight to the throne of grace singing

Hosanna

glory unto the lamb

Let's give her something

to give her hope

Read more >

Simple is Not Enough

Simple folk, with simple beliefs, simple habits

and simple lives.

Hard working, God fearing, narrow minded and

often cold blooded.

To live a life so closed and empty of human warmth

must be so soul destroying.

Living by your principles and your delusions.

There has to be more,

There is more,

You could have so much more.

A life that is fulfilling.

A life that contains warmth of human feelings

and love.

Reach out!

Drop your pitch fork and principles,

Grasp a life you are missing out on.

Before it is too late.

Gothic Guignol

The pitchfork’s pale/the church is paler

faces steely, occult violence/palest still

all gothic grimness in the American shale

you can see how the overtmurderousness

can spill and then refill,

these are not undertones of unintended massacre

this is an undivined madness

a cult of deadening souls

determined to be devoted to excess

so why do we love its expressiveness

the death upon death and death

of the destroyer zealot-a'-threatess

the warrior queen Kali the skull-wearer

who loves her man-o'-god

the battleship bully with Poseidon's rod

why do we hail them

these quasi-sacred Shiva shems

perhaps just apothegms

why don’t we name them/not myth

trump and bush and hoover

jefferson and his Monticello slaves

doyens of depraved democracy

why don’t we shame them

these acolytes of a-dolts and the reichs?

Nobody’s Dream

Two people pitchforked into,

A world of endless work,

Joy and love bleached out,

Worn and faded with drudgery,

Toiling, day after day,

To make ends meets,

To feed a family, created in love,

But raised on,

Home grown produce and sacrifice,

No Gothic horror can compare,

With the haunting, ghostly fear,

Of hunger and homelessness,

A spectre forever on the horizon,

Shoulder to shoulder,

With grim determination,

They face adversity,

Sharing, forever, always together,

The humdrum and eternal human nightmare.

We won’t sell

I don't know when he balded, it must have been a while. When we married, he still was a kind man, good-hearted and of hopeful spirits. That was before the crisis, as the paper calls it. I do not complain, we are getting along. There is work for two other men on the farm, the boys learn the word of God every Sunday afternoon.

As far as I can think, times have never been easy around here, but we wouldn't worry, wouldn't allow sorrow in our honest home. The Lord may lead us, he used to say. Now he speaks of rougher times, I see them deepen the lines down his cheeks and his chin. We don't sell a peck of wheat for what we used to.

The Bickermans have given up, he groans, sold their land to the corporation. What's a man without his land, he shouts, where should he live? We won't sell, I calm him, as he's forcing a laugh. We've tilled this land in four generations, we won't sell. Let the boys learn a profession, we can endure.

We are getting older, he objects, harsh fingers rubbing his forehead. Yes, we always have, and we've always strived. It is a new time, a new land. Let the boys learn, we will settle with what we have. We won't sell.

Impressions

Express lunch tomorrow, pitchfork confit pork belly, green papaya, curry sauce pitchfork,

but you probably knew that?

I just bought pitchfork tickets to a pitchfork fuc*ing Tame Impala concert in Israel,

but you probably knew that.

It’s not pitchfork hard to be ahead of pitchfork in the music game,

but you probably knew that?

Jon Bunch pictured pitchfork center,

but you probably knew that.

Pitchfork news: Matmos share pitchfork psychedelic Excerpt Three,

but you probably knew that?

Watch the trailer for pitchfork Don Cheadle's Miles Davis pitchfork film,

but you probably knew that.

Big Boi pitchfork announces year-long Las Vegas pitchfork residency,

but you probably knew that?

Bernie Sanders ends Iowa Caucus speech with David Bowie's Starman pitchfork,

but you probably knew that.

Sicko Mobb pitchfork drop Super Saiyan pitchfork,

but you probably knew that?

Pitchfork sick of watching George con my fellow hard working Albertans with pitchfork guru-isms,

but you probably knew that.

Some pitchfork smoked shoulders and cardio at courtesy of pitchfork the deer,

but you probably knew that?

Read more >

What will the neighbours say?

This is the last straw for Mary.

He knows it, too.

They stand there anyway, the semblance of innocence.

It won't last.

Word gets out like it always does.

Even when nobody ever says anything.

People used to smile when they walked by.

Now, steel eyes send shivers.

Still, they stand firm.

She smiled actually, once.

It was like a rainbow under a waterfall.

Not built to last.

Words aren't spoken in this house.

As if meaning didn't matter; only doing.

The turning over of hay.

Until the last straw.

GRANITE

Granite.

That’s what he reminds me of.

Hard. Inflexible. Implacable.

She’s only a child, I plead.

Foolishness is bound up in the heart of a child,

And the rod of correction will drive it away.

His stoic response.

Her eyes water as it dawns on her.

He will never forgive me will he, Ma?

I wring my hands and speak again.

At least let her in.

Let her put her feet up,

And have a cup of tea.

She looks terribly weary.

His grasps his pitchfork tighter

And my heart constricts.

If I cannot reach him with my words,

Then all is lost, for my hands have lost their touch.

Her belly heaves as she backs away,

Sobs echo from deep within.

Her hands reach out to steady herself,

As she staggers down the unpaved path.

I have no more tears left.

I utter pleas no longer.

For what difference would it make?

He is what he is.

Granite.

post-what?

all the bits collected,gathered up. the waste is the environment now

and remnants of life are the thrown away left-overs.

washed and polished, artists bundle them together, or

create little pieces of reclaimed

realness from how the world once was.

here we are. the penultimate existence.

sculptures of nature,

rotting.

Forks

Forks are sometimes

other peoples' daughters -

other peoples' daughters

turned into forks.

Forks that stand with

parents for a photograph,

prongs raised up like hallelujah.

Cameo

This is going to sound weird, she said, the first timeI met her. I have a photo of me at that age

and we look exactly the same. We were the same

age, so it was reasonable, given

fashions, that our childhood photographs would share

a look; two eight-year-old girls would share

some resemblance in the 80s. The only difference was,

I was cradling my baby brother

in the photograph, she was about to marry him.

But it was God's will. Same as it was

God's will when they moved into my house

until they could find a place together.

And it was God's will I slept in the lounge

so that they could have my bedroom,

her coming down with her hair

disheveled, like she owned the place. His

will we were at each others' throats.

But now I think, thank God

she came between us to save me

from fraternity.

Harvest

there were the leanyears, wrecked

nights, fevered

infants, blighted

fields, harrying

winds, we grew

twinned, slender

as needles, abraded

then smoothed,

upright as oaks,

silent as drapes,

my heart breathes

a hum that you,

sympathetic tine,

vibrate in reply

a ventricle beat,

a rod against

the lightning.

FREEDOM

We are not to be distracted or negotiated with.

We are settled in our utility.

If you have come here to broaden our minds,

With your questions and your silence doing the work,

You will feel something you did not expect.

You will carry away the marks on your skin.

What did you think we were going to say?

Look at us. Look around you. This is it,

My friend, the point you turn around,

Go home to spread the word of our welcome.

We want to share it with everyone.

We want to teach the world our ways.

We are done with being alone.

We are done with being alone.

American Gothic

Unspeakable, the past,

but he won't be here long.

Yellow as an old quince

and she knows why.

He's got the shakes

and she knows why,

But the pitchfork helps.

Malice clutches her heart.

Sundays are hard,

church is hard.

but she hasn't got long to wait now.

My wife is Althaea

Yes sir, we live right here in Hayesville Iowa.

Lived here all our lives, never ever left the State.

Travis... and my wife is Althaea.

Met at school, so long times now.

Sure, we saw them posters and heard a lot on the radio.

No sir, we never had no television.

Republican all our lives.

No sir, Caucuses ain’t for plain folk like us.

We just finished toasting some marshmallows.

Acts of Silence

I watch you look at me. Your eyes say nothing that I will respond to. I am a student of your pupils so in this knowledge of the unseen we are equal.

I feel her eyes swivel with the choking of suppressed speech that is not kindness, regret, pity or even indecision. She taught me the word inchoate. Her carefully punctuated not-looking sprung between my words from my offset. When she folded the clothes of rebellion without comment. As she counted the lashes of punishment without numbers, whilst mentally choosing the menus of reflected choking that surged from my mouth in silence. When she was made into you.

See your eyes. See her eyes. I cannot use my eyes to unsee the unsaid. I cannot speak to puppets or mime artists even if I can understand the artifice, translate the gestures. We share the same lips. Thinly disguised as family bonds. Invisible assertions of nothing. For you can look and not look and still I will not speak.

Burn

The artist suggested her husband hold a pitchfork: the artist wanted to paint a portrait of authentic hard working people. She fetched her husband’s pitchfork from the barn, but before she carried it out she scrubbed away the rust.

She prickled with delight when the artist positioned them beneath their arched window. Asked to find a comfortable position she placed her calloused hands against her black dress, underneath her apron. It suited her husband to be silent while the artist painted: since their daughter died from the fever her husband only spoke in his sleep.

As she stood in the heat she heard horns crack through dry skull bone.

That night, upstairs, her husband stripped to the waist, scrubbed the dirt that wasn't there. She raised the pitchfork and beat his arms and back. Moments later she guided him to the chair, bathed the welts in cool water by the light of the arched window.

Downstairs she snapped the pitchfork across her legs. Her face burned as the wood spat and the spikes blackened in the fire.

Common Sense

Her father had always saidone must look forward, not back,

and with steady eyes,

bearing the facts in mind, and probabilities,

making a plan and a second plan,

putting a little aside for tomorrow,

wasting and wanting not—

and although one stray

lock curled often out towards

what was not

(some romantic dream)

nevertheless she did her duty as was proper,

combed her hair and kept the house and tried faithfully

to take no thought for today.

The last fork

I was shifting the books From shelves to shelves Those letters from the first cry, growing black to grey With dusts of emotions

Slowly I shifted the whole house One by one All rooms Nothing left as mine Or yours… Except the last feelings Lingering in the lost mind

Did I forget something, Or I just remembering now?

When did you last say? We are alive Alive from the birth of time

Just like The house becomes the grave Grave becomes the temple Temple becomes the vast blue space

And then comes alive the rain

Then me

Then you

Read more >Re-imagining a piece of property

Rural Iowa, late nineteenth century, A tiny house stands unremarkable like the others And largely forgotten in the community. Then a painter is shown around the town and finds it inspiring And worth painting. This property gets immortalized as the American Gothic House By Grant Wood, in the August 1930. The small Dibble House imitates/modifies the Gothic style By incorporating new features like a window in a light frame house Mixing tradition with innovation. The improvised style suites their purpose for showing novelty. Wood re-imagines the commonplace and paints the house As per his inner dictates. His sister and dentist model for his artistic eyes The pitchfork The clothes The stern expressions of a hardy couple Working on the earth for survival Capture the dust from national architecture and history In a single frame than the archives. Two different segments of time get blended on this vibrant canvas. And so is born, out of this careful fusion and selection, a great piece of popular art That has put Iowa on international artistic circuits.

I’s tell a story of failed tongues

Not anyone lived in tall-house behind sleep town. With gossiping silence and curtains twitch frown. Nobody said murderer’s sh(r)ine. Kids changing sides, no ginger-knock down-time.

Then someone didn’t post fear through their box. Said faceless enigmas, swallowing frogs. Nobody set fire to barn hay of life. Folks ignored smoke, polished fork and sharp knife.

When no-one shout came in red angry face truck, Sheriff a smirking smiles shot out of luck. Nobody scuffled with translation that cost. Inmates made space another youth lost.

That anytime passed aged wrinkled skin bent. Jailors blind to misjustice life solitary spent. Nobody’s wife came release day to love. Back to that house – pigs, straw and ring dove.

Let sometime prove whispers, trust seeping come. Truth fighters pride – help to those some. Nobody’s victim, a lesson too late. Community language, difference love hate.

You Can’t Go Home Again

You can't move in again. Of course I'll give you a meal. Wait here with Howard and I'll make a picnic and we'll eat on a blanket on the front lawn. No, I'm sorry but I rented your room out to Howard. The couch is not available. Why? It's just not. You should have stayed in school or at least kept your job until you found your direction. Tough love? No, I wouldn't call it that. I would call it 'Tough Life" and we all have to go through it. I can give you money for the bus and a meal and also a stamped postcard so you can keep me posted on where you light. No. I can't give you your thirtieth birthday check early. It's because I love you--not that I don't love you. What about the picnic?

I See Everything

With each tine, I have plucked the trinity of you. Heart, mind, life - I have dug at your wildness, uprooted the plagues of desire. A puritan life does not flourish in wildflower meadows, is not Godly, not seemly, of no proper use. With the eyes in the back of my head, I see you, droop lines round the killed blush of your tight mouth. You look at yourself in the lenses, vain as Cassiopeia, mourning the time when your hair spilled down your spine like sin, I bet. I feel you, hating me behind my back, much good may it do you. Later we will talk about the lace you have put at the upstairs window. Inside the pinched slit of my lip-less trap, I am grinding my teeth to dust. I will cure you yet, woman. That loose curl, making a serpent behind your ear - I know you are taking pleasure from its touching of your neck.

The Bed Chase

“She stabbed the cleaning lady so I had to take the fork off her.” “Stabbed?” “Not hard. She blamed her for breaking the plate.” “And did she? Break the plate?” “I don’t think so, but I’m putting the knives and forks away. We’ll stick to spoons.” My father looks me full in the face. He looks ashamed. So this is old age. This is the shit that happens. Mum won’t meet my eyes. She’s not ageing well. Not a 21st century, trimmed grey hair, licence fee paid for, free bus pass, full pension, glucosamine tablets and a cruise booked for summer type of ageing. Her grip on reality is twisted and everything else is stiff, unbending, angular. Rigid fused spine, stiff neck, right hand locked inwards at ninety degrees where she broke her wrist and the doctors didn’t do a good job setting it - why bother with the demented ones when there’s so many young sane people in the waiting room. My mother is now sullen, fiddling with a lock of unwashed grey hair escaping from her ponytail, wanting to row with her husband but already forgetting why she is angry. My father holds onto the fork with white knuckles. I need to erase this ridiculous moment in time. Because moments become memories and I don’t want this one. I say: “Mum, remember how we would make make the beds together in the morning when I was little, before we got the duvets? How we stood opposite each other and pulled up the sheet to meet the pillows then we’d race round to the other side and whoever pulled up the eiderdown up first was the winner.” I say: “Mum remember when we did the bed chase?” But she won’t look at me.

As Clean as Wright’s Coal Tar Soap

I know a woman who actually cleans the dirt off a bar of soap. Her husband is a clean man, too; always smells of Wright’s Coal Tar. Spends his days on knobbly knees planting seed against the will of God’s own wind. His only mistress is the land — widely indifferent to his wife, who dreams of the day when his manhood ploughs more than silty soil. And there they stand, the strangest of company, waiting for the other to make a first move.

The Proposal

Although the sky was blue, the clouds hung heavy as lead, and the air was close and oppressive. Gus felt as though his collar was glued to his neck, and could scarcely breath, but composed and cool, Marina and Mr Allen seemed not to notice the heat. Marina stood slightly behind her father, and Gus smiled at her, assuming a bravery he did not feel. Marina stared back at him, her expression unreadable. Saul Allen waited silently: his spine, like the pitchfork in his hand, erect and rigid. Gus swallowed convulsively, his mouth dry with mounting fear. Finally he summoned up the courage to speak. 'I mean no disrespect, Mr Allen, sir,' he said, his voice sounding strange in his ears. ‘I…I love your daughter: I believe she loves me. I’d like to marry her. I've come to ask your permission, and, I hope, receive your blessing.' For a long moment Mr Allen gave no sign that he had even heard what Gus had said. When he spoke, his voice was as dry as dust swirling over barren land. ‘Love…love…you come here and talk to me of love? My daughter is a respectable girl: d’you think for one minute I would hand her over to a no good hill-billy like you?’ Ignoring the strangled sob from behind him, Saul Allen’s hand tightened into a fist around the pitchfork. He shook it in Gus’s face. ‘Dare to set foot on my land again, and you’ll answer to this,’ he snarled.

Breadwinner

He wakes up in the early parts of the morning, When the rest of his house is sound asleep So he can put in the extra hours for the sweet dreams of his family.

His children never sees his defeat Nor his wife sees the pain. He masks his troubles in front of his family Trying his best to hide his discomfort.

When the barns are empty and the livestock is dying, The smile upon his childrens' faces And the full stomachs in his house Gives this man another reason to go on.

As he lays down to rest He looks to the corner of the room Where his pitchfork stands Unsure if he will have the energy To go on tomorrow He bids a goodnight to his companion For today his work was done.

Now We Both Know

Not once did her eyes break from distant look. Nor her head move with the slightest of twitches. Here I stand transfixed, frozen it time with the truth. My eyes see her every non move yet they pierce this painter of ruin. Everything has changed and nothing will be the same. Darling I want to take an art class, she said.

Death of a Marriage

There was a time when I looked at you with eyes full of adoration--full of innocence. But now the light in my eyes has dimmed with the darkness of our murdered love. How can I say that I love you when I cannot bear your touch?... when I cannot meet your eyes? How can I go on living this lie? I must confess-- The love I had for you is gone, banished, forced never to return. We cannot forget the past any more than we can predict the future. And when we said, "Until death do us part," were we thinking of a physical death? or of a death of the spirit--a death of our love? Because I have been dead for years inside the cold recesses of my heart. In that powerful chamber, so full of the ability to circulate life throughout the body, I feel--nothing.

The Life You

The life you live is up to you. The life you make is one you choose. The life you live can make you ponder. The life you live is full of wonder. The life you live is all your own. You can be a doctor, a lawyer, a writer, an athlete, a musician, But whatever you choose, The life you live should be the life you want to live. The life I live is quite my own. My wife, my farm, my children, my crops. The life I live may be simple. But the life I live is all my own.

The Attic

The stranger makes his way back to his car. He holds his phone up to his ear as he walks. The way his shoulders slump, and the anxious way he keeps glancing back at the old couple seem to communicate his defeat. Still the old couple stand, seemingly ready to defend their simple home from what little threat the stranger could muster.

"I don' like it, father. This is the third time he's a come askin'," Mother whispers leaning towards him.

Father is silent, as always. Father watches as always.

Mother waits until the car fades from view before glancing back at the attic window. The faded gray curtains, broken only by the now cream-colored sun worn dots, remains still.

"He stares too hard for my likin'. She knows a better than ta raise a fit when company is by. Do ya think she was at the window?"

Father turned his stare to the window. He watched, and listened.

Mother nodded after a moment.

"Ya righ' Father. She know betta, and if she had shown her pretty face I'm sure we woulda seen it in that stranger's eyes..."

Father began to walk towards the house. Mother knew he was upset, but it was no use trying to reason with him. That stranger had been by three times now, he must of known something.

"Now father, you know she hae so little to spare these days. You only go takin' what she can give you now."

Father put down his pitchfork and went inside.

Read more >Timeless

Soothing sounds of wind coasting through the trees. Leaving no leaf or branch untouched with its soft touch. The farmers life comes with labor intensive work, but the reward is peace of mind. Nature all around. Unlike nature in other areas of life when it comes to the life on the farm nature is how you learn about the world. Everything that people know about the world comes from these simple ideas that have been around since the start of what we call life. These lessons taught by dirt, trees, wind, moon and sun. Timeless lessons of patience and virtue. All of the seasons play their part, all various types of weather and all temperature. Understanding nature means to understand ourselves. These are the ideas we were bred on. To know these things is to understand the timeless wisdom that is the world.

Lost Love

She could not love him Like she once did

When May blossom Drifted through the Orchard Starred the green carpet Their embroidered bed

Or in the first summer Hidden by the maize A Pale green veil Enclosing each kiss

He had held her hand While she wept in the chamber And the nurse left them quietly For long hours and long days

But the snow came And coldness found its way Through thin slats And thin lines grew

For nights without a lantern Don't show in the alley A lithe frocked figure Stealing embrace

Read more >Ignorance

'Ignore them' 'They do not belong here' 'They should not be here' 'What are they doing here?' 'Why don't they go back to where they come from? - send them back!' 'Don't encourage them' 'Close the curtain' 'Lock the door' 'Turn on the TV' 'What are they doing?' 'Where do they thing they are going?' 'What do they want from us?' 'Why here?' 'Can't they stay in their own country?' 'They look strange.' 'They look different' 'What is their God?' 'What kind of language is that?'

('Oh, he's crying.' 'He's a father.' 'Her son has drowned as they escaped the war' 'So has his wife.'

Read more >The Negotiator

“This pitch-fork will bring you prosperity and food,” declared Boris, handing his son, Frank, the tool he would use for the rest of his life.

Philippa watched her new husband take the fork and press the points with his thumbs.

“You’re the man of your house now,” continued Boris. “With this you will always be able to find what you need in the land.”

“Yes Papa,” nodded Frank.

Philippa couldn’t help but notice the tears welling in Frank’s mother’s eyes. Were they tears of joy that her son was married? Or tears of sadness that he was leaving? She held out her hand to the woman as Boris pulled Frank aside to embrace him.

“I will look after him Nancy,” she said, smiling and hoping to reassure her. Philippa’s mother had gone to great lengths to explain to her the new duties that as a wife she would have to learn – being a peace keeper and a diplomat.

“If you want to look after my son, take him away,” whispered a teary-eyed Nancy.

“Pardon?” whispered Philippa.

“Throw the pitch-fork away. Make him a suit and follow him to the city. He’s meant for more than turnips,” she hurriedly explained as her lips neared Philippa’s left ear. Read more >

We Dream

I was young and believed all the dreams young girls are told. My pictures books were filled with beautiful princesses rescued from lives of servitude by handsome princes. And, as children… well, as children we dream. We are taught to believe in Santa Claus, or if not Santa Claus then God, and Jesus, and the Disciples, and Moses, and burning bushes, tablets of commandments the defiance of which will leave us burning in the dark unknown.

My childhood was early mornings in the shed. Wrapped in my father’s overcoat, the scratch of wool against my neck, I blew smoke rings in the cold morning air. On the darkest mornings, I stumbled from the cot I shared with Celia, to the basin where I scooped just enough water to wash. Then out to the shed for milking. On the days when my fingers stopped working from the cold, I would press my palms against the animal’s side, my cheek against hers, and take her warmth. I was waiting for my prince.

It was I and Celia who ran the farm after Mama died; yes, Papa was in the field, buying cows, selling pigs, taking harvest to market, but it was us girls who made things go. We drove the wagon to town to get the provisions and animal feed, the flour, milk, sugar, medicine for papa’s cough. No longer going to school, our classroom was now the barn: our lessons those of survival. Miss Pratt had begged Papa to send us back, but “What good would school be?” he asked. “A waste of time for girls.”

Read more >sons

their sons' names are on World War 2 memorials in small towns around Pocahontas they were miners they had no mountainside grave where endless coal trains rumbled

Clarissa

Howdy, my name’s Clarissa. I’m Ma and Pa’s favourite. The representative of the three pronged trinity - truth, justice, redemption. They keep me clean, shiny and sharp. Just like the day they bought me. I know my Ma and Pa are the righteous ones, yes siree. Every Sunday they go to church without fail. Their clothes may be worn, but nothing is ever out of place. They don’t whoop and holler, not like some of their far flung neighbours. They utter their prayers under their breaths. The Lord likes it that way. He can tell who’s the most deserving. He’s not deaf.

I got a couple of brothers, but they don’t scar as good as me. They know their place and I know mine. That’s what Ma and Pa say. It’s a shame other folks don’t act this way too. You know, like the ones passing through, who think they got the right to stare at my Ma and Pa. I don’t like it one bit.

But the worse kind, are those sneaky property prospectors claiming to be the lost. Knocking so hard on our door when Ma’s in the middle of her daily chores, making it shudder. Pa’s out back, the pigs all the company he needs, breaking his back with one of my brothers. Scraping and digging, digging and scraping until the soil's just right.

They think Ma’s house is quaint. Looks like it’s outta some old movie. Beady eyes scanning and calculating. Ma says nothing. Silence is her weapon, learnt that long ago. She enjoys it when they start to get twitchy, giggle to themselves. A thin film of sweat on their greedy brows.

Read more >American Gothick

That lancet window under the tympanum with its Y-tracery–

Not so much Gothic, with its 'barbarous German style' (cf. Chartres, Salisbury, Rievaulx)

As Gothick: Strawberry Hill, Horace Walpole, The Castle of Otranto.

For this man, believing he has fashioned his house after the worshipful stone monuments of his forefathers,

It must have come as a shock to find his wooden villa has become a horror story.

See pitchfork, the black pall curtain; Strawberry Hell?

American Gothic Century

He remembers when his mother’s geranium was the homestead’s only grace. She grew it from a slip she brought out from Sweden, when she and his father arrived, way back, just after the war between the states. Its purple blotched leaves, like fading bruises, have survived locust swarms, tornadoes, the plummeting price of wheat.

She will remember a blue and cream Chevy, rounded in front, sharply finned in the rear. It hulks in the dooryard, shrinking the farmhouse further into the background. There’s no room in the picture anymore for the geranium, but it might have disappeared anyway. Lately it hasn’t flowered so much.

He remembers returning home from the fields the day his mother hung the lace curtain in the second story window. From afar, it appeared like snow falling and drifting, fluttering a cool ghost-like welcome.

She will remember how the second story window looks like an eye, aging, growing milky and sightless. It makes her feel as though God is watching her, malevolently or benevolently, she is not sure which. She could hang new curtains, something brighter, more modern, but they would not alter the church-like certainty of the window itself.

He remembers his mother’s cameo brooch that she wore on Sundays, even when the weather was too stormy to go into town for church. She used to let him hold it for a brief moment, while she was still fastening her white collar under her chin. He liked the weight of it in his palm, the chalky topography of the figured head under his thumb.

Read more >American Paradox

Thousands of miles away, In another place and another time, Familiar in its austerity, Portrait of hard labour and domesticity Of colonial farmers - and yet The grim-faced puritans, Small-town bible thumpers That scared me as a child, As an adult With a love of horror And a distaste of kitschy Americana, Present me with questions: Who are these tintype people From an obscure family album? A satire of small-town life Or a reassuring image Of steadfast pioneer spirit?

What The Eye Don’t See

Rats - in the bathroom in the tack room in the back room

in the shower, in her bed unstuffing her pillow unpicking stitches in his quilt

down in the kitchen in the saucepans in the drawers

sniffing out a bag of flour licking out the dripping bowl catching

their whiskered features in her granny's silver spoons. However, in the smaller picture,

not one spot of rat's blood on the windows on his pitchfork

in her hair or on his specs. Not one flattened rodent

underfoot. Not one small expiring body on the threshold. Ah!

but what those rats don't know is that this solemn couple have recently bought shares in Warfarin.

CURSED

"Now Priscilla, you go on now and plow the fields, y'hear? I'll be moving the hay."

"If you want, I'll be chopping some firewood too, Pa."

"You don't go doing that... that's men's work." A sigh. "And since we don't got no other men around, I guess that just leaves me."

It's always like this. Every day we tend to the earth surrounding our small home. Pa does chores he considers 'men's work', and gives me what he deems the lighter task. Was hard enough trying to convince him I could plow the fields, move the hay, rustle up the cattle. Anything to get out of fixin up the house all damn day.

He was getting old, Pa. But he was so stubborn to realize all these activities were straining him, before he finally relented.

"If only you was a boy..." I know he never said it, at least to me personally, but I could feel it sure as anything. Havin no sons or no man willing to be my husband, I assume Pa was at a loss of what to do with me, except be a farmhand.

Must've been embarrassing for him. Being seen by our neighbors as "Tom, the man who couldn't marry his daughter off and find a decent man to inherit this plot" or "Tom, whose life was so unfortunate as to give him a girl and nothin else."

He was cursed with a me, and thus no legacy in his mind.

Or maybe I was the one who was cursed, having to live my life as a constant reminder that I only survive to keep my father unhappy.

Who knows? Perhaps it's both. One and the same.

Read more >Prudence and a Pitchfork

We came here to be free, My mother said. They Trekked to this place To farm and to leave me Landlocked. He Took me up. We Persevered and ploughed. I thee'd and thou'd, as expected. He grew spare and dessicated, I was young once and fair Like the old county. I knew how to smile once, Now I am hardly there. You see him, and work And church and barn And sacrifice. My mother said we came here To be free. That did not happen, For her or me.

The Cameo

He had given her the cameo brooch on their wedding day, pinning it at her throat, piercing the fabric of her wedding dress with its high-necked lace ruffle, his hands not yet roughened and reddened by decades of clutching a spade, a pitchfork, a horse's rein. It had been a warm day, the clouds heavy and low over the church's pointed cross, and she had been embarrassed by the sweat that trickled beneath her white dress; hot from the weather, and from the eyes on her, and from something else too, not yet recognised.

It was my mother's brooch, he had told her. She knew it to be true from the photo of his mother he kept in the ornate and oval frame that stood on their mantelpiece. In the studio portrait, the cameo brooch was pinned at the neck of his mother's black bombazine dress, beneath a face that stared out so stern and severe that she could never picture her dead mother-in-law as anything other than cross and in black and white, although according to her husband the woman in the photo had been a happy soul who had smiled often and sang to him and favoured bright colours.

It belonged to my mother, he had said, and one day it will belong to our daughters too.

But the daughters had died, one after the other. Born pink and plump with a piercing scream that matched her own, each one grew pale and pinched and pitiful. They slipped out of her arms and into the churchyard to join the grandmother they had never met, while she wore the cameo brooch at the neck of her black linen dress.

Read more >OUTBREAK

The huge isolation marquee with fitted airlocks tinted the pale pink of the Beaux-Art architecture with a sort of cyan opalescence. He stepped through the first seal and nodded to the camera, itself encased in protective plastic incorporating electromagnetic and radiation filters. They were taking no chances with this one: biological or emission-based, this could not be allowed to become and epidemic.

Anthony Zale, PsyD, looked around at the decontamination array and took a deep breath, something he had been schooled not to do. He had to fight off the momentary dizziness.

“You did it didn’t you?” his ex-wife’s voice on the communicator accused. He chose not to respond and stepped through the second lock, careful to seal all behind him.