- Vol. 04

- Chapter 04

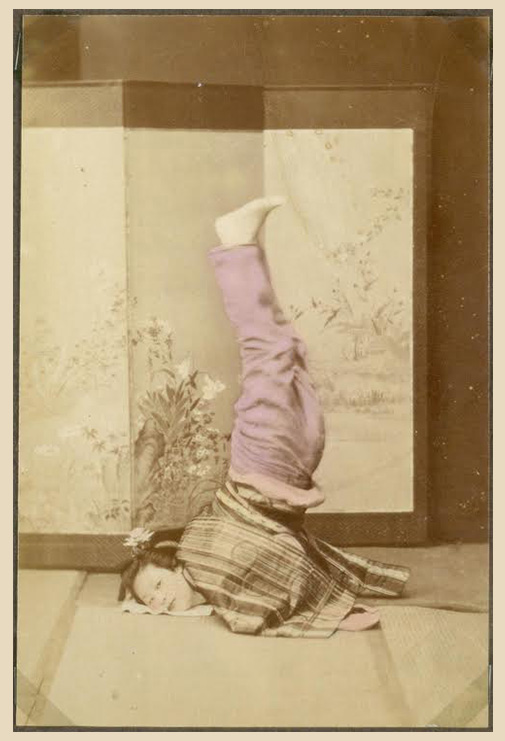

Image by National Museum of Denmark

Tilted Axis

There was a single photo on her fridge surrounded by a kitschy set of fridge magnets. There was a rubbery marijuana leaf from Amsterdam, a tiny plasticy bottle of wine from Bordeaux, and a rectangular plastic coated photo of Heroes Square in Budapest. She didn’t like to think of herself as a tourist but she enjoyed the way they triggered memories of tangible moments in time, particular geographies of the heart.*

From the telephone box, through the cards advertising bodies and services of pleasure, she could look out across the canal to a bar on fire with neon. The coins clinked into the slot with three clink clink clinks and the dial tone pealed in her ear before a cough broke the trill and threw her, she lost her place. Hello? She said in a stoned drawl. A distant static came down the line and a distant sound of feet pacing across a floor. It’s me, I’m waiting she added. The feet came to a sudden rest.

*

The café spilled out into the muggy heat of the night. She had been signaling to the waitress from the wrong café for half an hour, the two recently empty wine glasses heavy in her hand as she waved them fruitlessly in the air. The woman at the next table was flicking through a brochure for luxury flats in the city, and after seeing her flailing, the woman put the brochure down and leaned over to her, he’s not coming back honey.

*

Tilted Axis

The square was slippery and deserted. Her jacket zipped up to her chin, she looked like a submarine’s periscope. This was the logical end to their interaction. He was intriguing enough to make her consider radically changing her life but not enough to make her actually do it. His body was a sounding board for her uncertainties. As the evening began to cling to the ornate structure of the square around her and the evening time traffic started to build in waves of honks and skids, she smiled. She knew he’d never come, but there was no way she would give him the satisfaction of not turning up to witness his absence.*

As a child, she had regularly sat bugging her Father in his study, bored of the weekend or a summer holiday. Above his long bulky desk was a grand map of the world that still showed empires and kingdoms, large swathes of territory of differing colours and topography. A nimble child, she would tip this strange ancient world on its head and survey it upside down.

‘Who decided the world should go that way up Dad?’ She pestered. He would look up momentarily from whatever work it was he was engrossed in.

‘Men. Usually men who had seen nothing of the world, but couldn’t face not being the centre of it.’

From then on, maps reminded her that you could change the world, merely by changing how you looked at it.