- Vol. 06

- Chapter 07

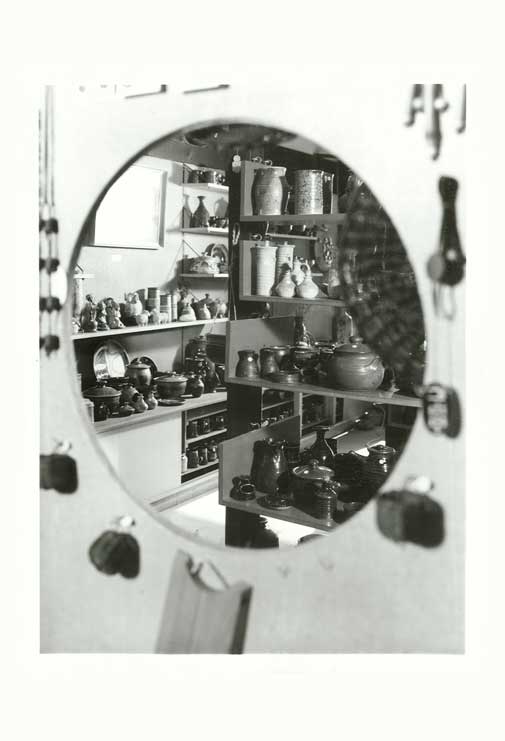

The Reflection

As a kid I loved to look in the backroom

mirror, small and round, surrounded by keys

and other mysterious tokens Grandma

wielded in the shop and the studio.

It was halfway up the wall: From my small

vantage point it looked like the porthole

in a cruise ship’s cabin in an old Forties flick.

I liked to look at myself in that mirror

but also to angle my chair or milk carton

so that I could see the image of the shop—

its shelves and rows and rows of bowls,

pitchers, plates, cups, stewpots, and teapots—

minus the reflection of my self-conscious face.

I preferred losing myself in the variegated rows

of pottery, in the glow of their glazed surfaces.

Their hollows held me—the many selves I might

become or could imagine. I was so young

that numbers overwhelmed me. The sheer

abundance in that reflection stayed the fear

I felt in the shop itself. There I worried

that I would jostle—or, worse, handle—a cup

or bowl or teapot and break it. I imagined

the floor littered with teapot spouts

and my own shattering in the face of adult

anger and the ravage of self-mortification.

The Reflection

Like those ceramic wonders, whether homely

and sturdy or elegant as heirloom china,

I was deceptively fragile. Like them I looked

solid but could fracture. And as it seemed for them,

so did it for me: the break—even the smallest—

undermined my worth, erased the glaze,

the handicraft, the beauty, as if only the perfect

deserved our admiration or had a claim on us.