- Vol. 08

- Chapter 09

THE PLAYER’S DAUGHTER

The girl at the bus stop only asked for her fare. I had no money, so I took her home. I told her my father had a car and he would drive her. Together, we walked the length of the dusty hedge inhaling the heavy summer scent – cow parsley, dogrose and honeysuckle. We were the same height, both small, but her clothes were too tight. Her grey trousers flapped at her bare ankles. We shared my Spangles and argued over the best flavours. We spoke about pop music, fights and brothers, and howled with laughter at it all. Her accent was strange. I didn’t ask her name, and she didn’t ask mine.

My mother looked flustered. She gave us fat slabs of gingerbread, thickly spread with butter. The girl ate three slices. I had none. When it was time to leave, my mother offered her my old bright blue slacks and told her to put them on. They were a little too baggy, but the girl held them up around her waist, as if afraid they would be snatched away, and said they fit. She looked pleased. She folded her own grey trousers into a tight roll and didn’t say thank you.

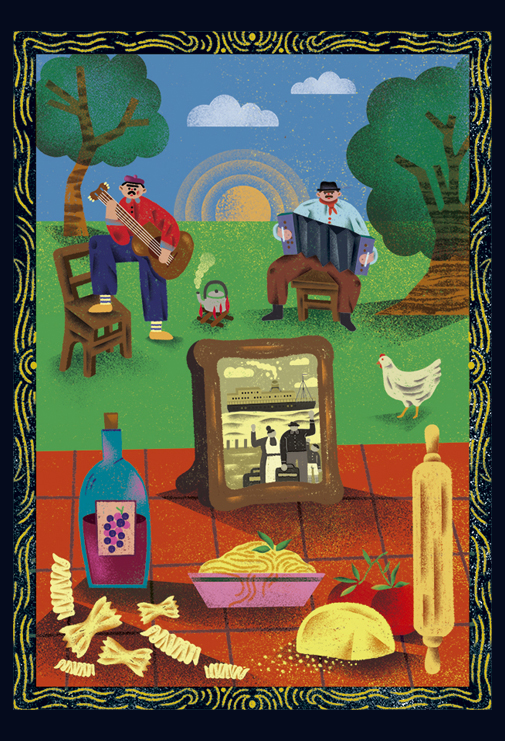

As we left, a look passed between my parents. I knew the look. It said trouble. Was I in trouble? I didn’t know why. We sat together on the back seat of my father’s car, quiet now. She seemed not to want to go home. I worried about “the look”. There was no more laughter. My father slowed as we passed the confusion of caravans, barking dogs and woodsmoke, but the girl told him no, she should go to the pub. Her Da, she said, would be in there. Playing guitar.