- Vol. 05

- Chapter 01

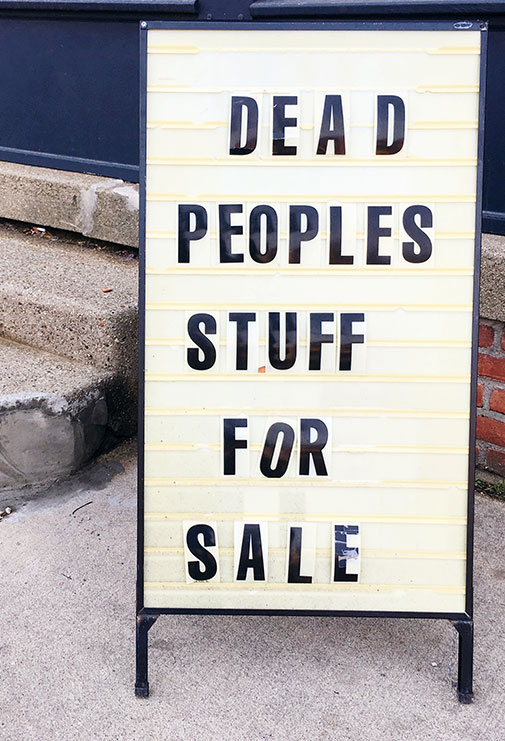

The Dead and Their Stuff

It was once thought there were two types of stuff – properly called ‘substances’: physical and mental. It is fashionable now to think there is only one.

I tend towards two.

To believe in one substance – the physical (and such is the fashion) – you must believe all life is reducible to properties that don’t in themselves contain life, and that somehow a certain volume of impersonal properties can create a living thing – in this instance, a person.

Some very eminent people no longer believe in personhood. Which means you can’t logically have dead persons, or their stuff - you just have things that are more or less that thing.

Other eminent people say you cannot believe or disbelieve in personhood without first agreeing a framework of personhood.

It might be that the collecting of stuff, whether from the living or dead, is proof of personhood, or at least stuff that is decided upon because of meaning or value – mental stuff.

*

In church halls, youth clubs, community centres, foldaway tables are arranged in a rectangle and the stuff of dead people is sold alongside the out-grown and the unwanted.

In galleries and bookshops physical stuff is sold that contains, either within or on its surface, mental stuff. And much of this comes from the dead.

There is a lot of ‘dead peoples stuff for sale’.

The Dead and Their Stuff

In art ... the highest prices are paid for the most extraordinary combinations of physical and mental stuff. And the highest prices tend to go for dead people’s work.

Art cannot be reduced to physical properties because art is a language and the meaning of words or the symbols of the language is not present in the materials that deliver the meaning.

As a writer, some of my mental stuff is rendered into existence by physical properties (ink, pixels, paper), but these properties in themselves do not contain the meaning of my mental stuff, they are merely a way of dispersing aspects of my personhood (imagination, judgement, insight) into the physical world, so that other mental stuff (readers) can apprehend the meaning (from the physical properties that don’t contain the meaning). (It’s quite something.)

In that way my personhood, or at least aspects of it, are for sale. This will still be the case when I’m dead.

*

It is because of all of the above that we have to interrogate the meaning of the missing apostrophe.

Does the writer want you to understand that he / she believes that life is a condition of possibility for the possession of stuff, and that by not including a possessive apostrophe their intention is to create a grammatical event that insists on this impossibility? I can only assume so. I mean, what other explanation is there?

It is clever stuff.