- Vol. 06

- Chapter 09

Spem in alium nunquam habui

Initially my mother objected not to you, but to the church.

“Michael, it’s hard enough to tell your father his meshuggeneh son is marrying, a— a—”

But she did own some very nice recordings of Bach made there, and Vivaldi, and she and my father believed in nothing so much as a period use of harpsichord, so in the end it didn’t matter. Years later, trimming the primroses in the back garden, you would tell me that before the ceremony my mother kissed you on the head and my father stomped on the glass a little and told you not to worry about my weak feet.

You were fixated on the church bit, and since you had made the news it’s not like we didn’t have the money. It wasn’t St. Martin-In-The-Fields at first, but when the kindly vicar called and told you the publicity would do ever so much to help their mission to the homeless, how were you supposed to refuse?

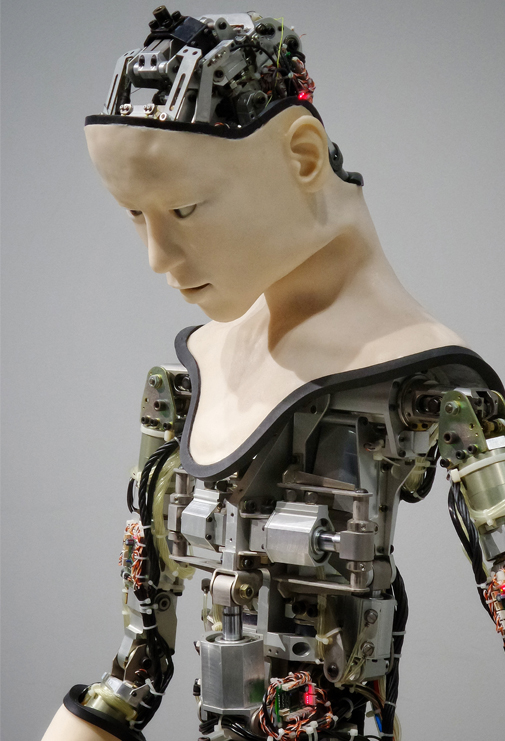

In the end you had a seven-foot cathedral veil, fresh irises, and boy choristers singing Tallis. The dress was a very standard UK size 8, you confessed, not without amusement that the Primary Investigator of our laboratory had attended to such things in your manufacture. He walked you down the aisle; it made sense in a way.

When we got to the altar we said the Three Laws first, back and forth to each other. We slid the rings onto each other’s hands, simple gold bands engraved with our names and the date we met, the date of your inception. If you asked me could I have predicted? No, of course not—not this, the nine or so minutes of mutual silence standing close to each other in the nave of the church, listening. Had the world been Lamarckian, you would have certainly developed the ability to let tears stream down your cheeks.

Spem in alium nunquam habui

In the end it was not what you were that astounded me, but who you had become, so unutterably different from I, who had soldered your very veins together. The way you inclined your head slightly to the Bishop in her robes, the way your voice quieted when you replied “and unto you.” The way you looked up at the round globes of the chandeliers in the Wren vaulting, a way I could not, and would probably never, understand.

Afterwards, at the reception you laughed at me, twinkling, as I stood mechanically in my old matriculation suit, so unlike your easy gyroscopic grace. You leaned into my shoulder before the first dance.

“Don’t say anything now, but I’ve promised your mother grandchildren.”