- Vol. 01

- Chapter 01

September 1940

Mum tied it on. ‘So they’ll know who you are,’ she said. Wearing half me clothes, the rest squeezed into a small suitcase, I felt like a badly wrapped parcel – but it didn’t feel much like Christmas. I bit me lip, pushed my fingernails into my palms until it hurt, glad I’d stopped biting them. Though I’d start again soon enough.

We were in the school playground first off. They gave us each a cardboard box. Thinking it was a present, some kids got all excited. I knew better: ‘Gas masks!’ I told the boy next to me; his face dropped.

From there we was herded on to buses that took us to Paddington station. Knuckles clenched, holding myself together, I didn’t shed a single tear. Others did: girls mostly, and mums. Not mine. Kissing me on the cheek mine told me ‘all that fresh air’ would do me good. ‘Like all those holidays we couldn’t afford thrown into one,’ she said, sniffin. And wiping her nose with her sleeve she was gone.

The train stopped at a place I couldn’t pronounce. I was nearly nine, but reading wasn’t my strong point. Though I was good at sums. Could add up well enough to know this didn’t add up to much of a holiday.

Last holiday we’d had was a day at the zoo. Seeing the gorillas and lions all penned in, I wanted to unlock their cages, let’em out. That’s how I felt: caged, trapped.

We stood in this drafty hall, a load of grownups looking over us like we was animals. ‘I’ll take this one!’ a tall, beefy woman said, picking up my suitcase, grabbing me hand, dragging me off.

September 1940

She looked at my label, told me her name and said little else, as we bumped along the winding wet roads. Gazing out at the empty gloom, I wanted to be magicked back to die in a bombing raid with Mum and Dad, or be crushed under a desk with Vincent and Raymond.

My ‘holiday’ lasted four years. I didn’t send any postcards. Just a handful of letters: a few words on bits of lined paper my custodians would give me, then take back again, checkin I’d not written anything untoward, before it popping into an envelope.

Mum and Dad came out of it unscathed. Should’ve been pleased, but I wasn’t. At least if Dad had lost a leg – like Raymond’s dad – or the flats had been flattened, it might’ve seemed worth it. Vincent, sounding as pompous as his pig-ugly father, reckoned he’d ‘had a good war.’ Mentioned how exciting it’d been only a few weeks back. He’s not moved far either.

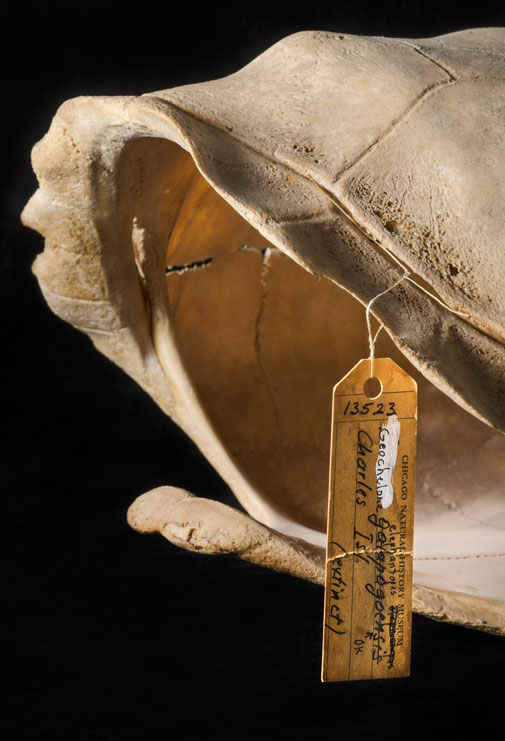

Wish I could’ve said the same. But the fascists weren’t just over there, y’know. Operation Pied Piper taught me to be wary of grown-ups. I clammed up after that. Pulled me head in, like those big tortoises I remember seeing at the zoo. Felt safer under that hard outer shell I’d developed.