- Vol. 08

- Chapter 09

Pizz-a

British tomatoes taste like water. Grown in a cold climate, not under the heat of a fierce sun. I dream of the Napoli tomatoes of my youth, picked off the vine, smelling like grass. I am heartsick for my homeland. I came here to make a new life in the 1950s, leaving poverty and hardship behind, but this is not what I expected. I found opportunities but left behind warmth, friendship and genuine smiles.

How can I make my pizza sauce with such poor ingredients? I take the trip to the wholesalers, I return dispirited. My customers don’t notice; they scan the menu with incomprehension at these strange, foreign foods and demand the familiar steak and chips.

Unlocking the restaurant, I stagger up the stairs, a crate of sad tomatoes in my arms. I await the evening trickle of customers: young families and an elderly gentleman, who comes in at 5pm to warm himself around an endless frothy coffee, waiting for his bus.

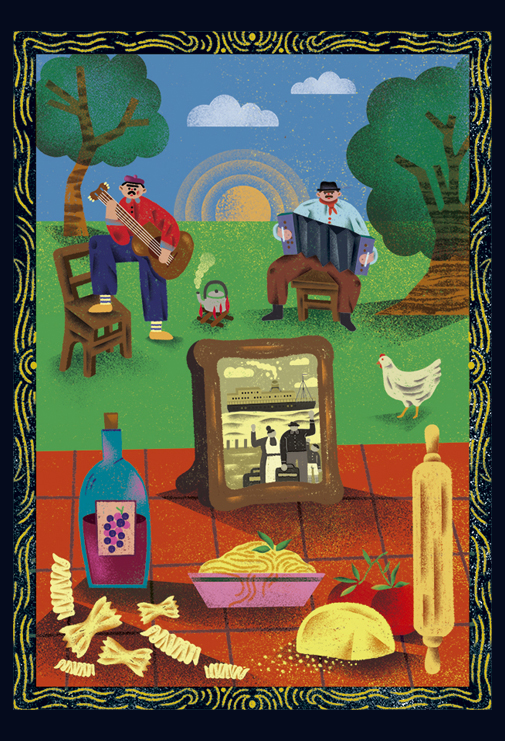

I allow myself a quick moment of pride for what I have created here. In England I have worked long, hard hours making bricks, sending money back to my family, putting aside a little each week to pay for this dream. The painted wall tiles depict Venice, and the country accordion player who reminds me of my village. The tables are covered with bright oilcloths and wine bottles crusted with candle wax. It’s not so bad. Time to make pizza. Maybe someone will try it this evening.

The young families have had their chips and tomato ketchup again, and the old man stares into his coffee. The pizza is cooked through, warm and crisp from the oven, filling the kitchen and the restaurant with its bready redolent scent. I will cut it into slices and offer these to customers, in the hope that I can whet their appetite for more.

Pizz-a

I approach the old man; “You like to try?”

Tentatively he takes a slice, “What is it?”

“Pizza,” I reply. “From my hometown of Napoli.”

He takes a bite, pulls a little face. “Pizz-a?” he states.

“You like?”

He nods slowly. Takes another bite. Raises his eyebrows.

“My problem is the tomatoes,” I suddenly find myself confiding. “I can’t get them with the right flavour like in Italy.”

He nods again, stands, leaves for his bus. I shrug my shoulders. Did he like it? Who can tell?

The next day as I approach the restaurant in the grey drizzle, I find the old man waiting for me in the doorway. I usher him inside, sit him down and make his coffee.

Shyly, he pulls a large container out of his shopping bag and hand it to me. “For the pizz-a,” he confides. The rich smell hits me before I see them. Fresh tomatoes, perfect, round and beautiful, and straight out of his greenhouse.

I clap him on the shoulder. He steps back, out of the reach of my impetuous hug, but gives me a smile.

British tomatoes taste like water. Grown in a cold climate, not under the heat of a fierce sun. I dream of the Napoli tomatoes of my youth, picked off the vine, smelling like grass. I am heartsick for my homeland. I came here to make a new life in the 1950s, leaving poverty and hardship behind, but this is not what I expected. I found opportunities but left behind warmth, friendship and genuine smiles.

Pizz-a

How can I make my pizza sauce with such poor ingredients? I take the trip to the wholesalers, I return dispirited. My customers don’t notice; they scan the menu with incomprehension at these strange, foreign foods and demand the familiar steak and chips.

Unlocking the restaurant, I stagger up the stairs, a crate of sad tomatoes in my arms. I await the evening trickle of customers: young families and an elderly gentleman, who comes in at 5pm to warm himself around an endless frothy coffee, waiting for his bus.

I allow myself a quick moment of pride for what I have created here. In England I have worked long, hard hours making bricks, sending money back to my family, putting aside a little each week to pay for this dream. The painted wall tiles depict Venice, and the country accordion player who reminds me of my village. The tables are covered with bright oilcloths and wine bottles crusted with candle wax. It’s not so bad. Time to make pizza. Maybe someone will try it this evening.

The young families have had their chips and tomato ketchup again, and the old man stares into his coffee. The pizza is cooked through, warm and crisp from the oven, filling the kitchen and the restaurant with its bready redolent scent. I will cut it into slices and offer these to customers, in the hope that I can whet their appetite for more.

I approach the old man; “You like to try?”

Tentatively he takes a slice, “What is it?”

“Pizza,” I reply. “From my hometown of Napoli.”

He takes a bite, pulls a little face. “Pizz-a?” he states.

“You like?”

Pizz-a

He nods slowly. Takes another bite. Raises his eyebrows.

“My problem is the tomatoes,” I suddenly find myself confiding. “I can’t get them with the right flavour like in Italy.”

He nods again, stands, leaves for his bus. I shrug my shoulders. Did he like it? Who can tell?

The next day as I approach the restaurant in the grey drizzle, I find the old man waiting for me in the doorway. I usher him inside, sit him down and make his coffee.

Shyly, he pulls a large container out of his shopping bag and hand it to me. “For the pizz-a,” he confides. The rich smell hits me before I see them. Fresh tomatoes, perfect, round and beautiful, and straight out of his greenhouse.

I clap him on the shoulder. He steps back, out of the reach of my impetuous hug, but gives me a smile.