- Vol. 06

- Chapter 02

MY GRANDFATHER’S FUCK-OFF BEARD

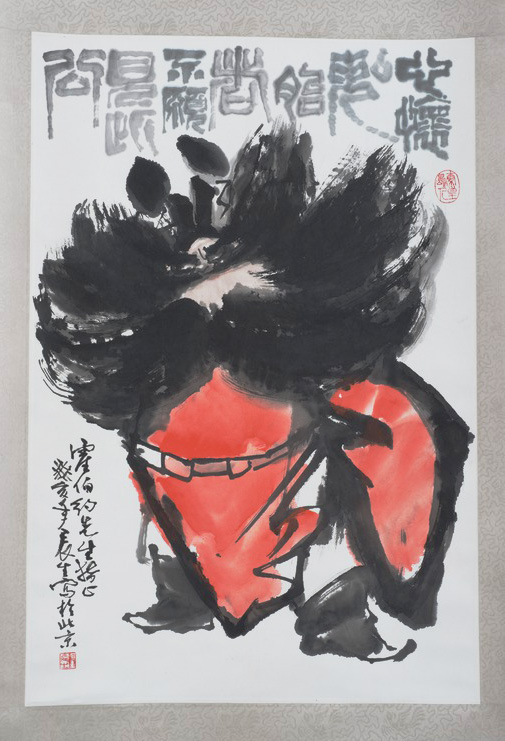

I remember when my grandfather used to fill the room where he was and his laughter shook walls and window glass, and he had to bend his head so as not to touch the ceiling. He looked far off then and his eyes were like distant stars or the blue flashing flames of gas fire and his hair was all shocked and torn and he had a big fuck-off beard – that’s what my father called it and my mother said my father should please mind his p’s and q’s in front of the children.

There’s a poem by Edward Lear about an old man with a beard and it reminds me of my grandfather – not because there were things living in my grandfather’s beard. No owls or hens or larks or wrens had made their nests there, but he kept things tucked into his beard so he knew where they were. If ever he needed a pen he’d run his fingers through the black tangled hair and produce as if by magic a burgundy coloured marble Stewart Conway fountain pen. He could do the same if you wanted money or Callard and Bowser toffees in their wrappers or toothpicks or bus timetables.

He’s old now – though I thought he was old then. Old as hills my mother says. Old as tram tickets says my father. He’s old now and shrunk to less than half his size and his beard is grey and yellow and thin as smoke and not pens or toothpicks but bread and biscuit crumbs now live in his beard and spiders and silver spittle threads unspooling when he is asleep in his chair and the chair seems to hold him even when he is not there, holds the shape of him like a giant cupped hand.

And when he speaks my grandfather’s voice is all breath and whisper and he leans towards me so he can hear me talking and he says to speak up; and his eyes are grey as unpolished silver or wet streets and I look for the blue that was in them once and now is gone.

MY GRANDFATHER’S FUCK-OFF BEARD

One day I think my grandfather will be as small as a mouse – a pink-eyed white-furred mouse with a thin limp tail – and then I will carry him oh so gentle in my pocket, feeding him shortbread petticoat tail pieces and the broken corners of toasted fruit loaf slices, and he will speak to me in singing pips and squeaks, the gossamer filaments of his whiskers twitching; and no one will believe that the mouse is my grandfather – not even my father or my mother. Indeed, my father will say I am tuppence halfpenny short of a fucking shilling and my mother will remind him again please to watch his p’s and q’s in front of the children.