- Vol. 06

- Chapter 07

Finding A Shape

When Barber Chua’s last client leaves, life in his shed begins.

He starts small and simple. An earthenware cup. Its wall is uneven, the surface too thick.

The next day he repeats making the same thing. More control in his throwing, the pottery wheel’s going slower. His mind goes to a boy who came with his uncle. The child sat quietly watching. Giving the boy a side glance, Barber Chua noticed he’d been staring at him. He stopped, gesturing for the boy to come closer.

‘He’s mute,’ the uncle grumbled.

‘You see this?’ Barber Chua said, ignoring the adult. The boy gazed at a straight razor he’d been holding in one hand, his eyes widening.

‘After my sister went, he's like that,’ sighed the uncle from the chair. ‘Run your finger through it, boy. Go on.’ Sitting on the wheel, he recalls the slight trembling of the boy’s chubby index finger while tracing the metal. He pulls his hand off it and a cup stands tall.

Another day, a merchant wearing a lost look on his face walks in. Barber Chua’s scissors hover over his head; he’s using a razor lightly to trim his sideburns. For the man needs not anything but a seat and a company. That day when the barber lights the kiln he places a large bowl with shallow bottom for firing – among others.

Ceramics is added to the repertoire. The small boy becomes his apprentice, tasked with sweeping the floor. The barber moves on teaching him how to sterilise the tools, sharpen the blades and wash the used towels. His aptness earns him various demonstrations of hair-cutting techniques. He tells the boy to think of a client’s head as a canvas to a painter. A barber’s marks are as distinctive as an artist’s.

Finding A Shape

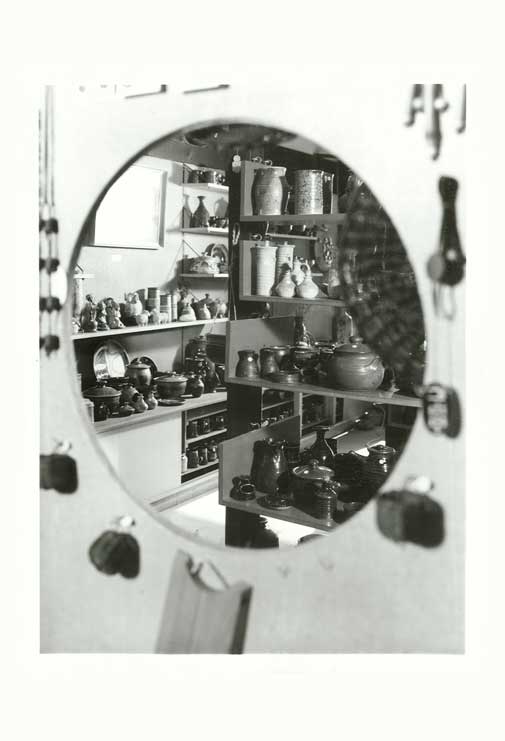

He trains the orphan how to move his hands and legs, turn his heels in melody and in time for precision. Once the boy works faster the barber’s potteries grow in shapes and colours.When the time comes that he can only stand shortly the then-boy takes over. Two village boys as assistants, one orphaned. The old barber, leaning on his stick, would study from his seat the rhythms of their joint motions. He'd rise from his seat to push down a hunched shoulder or pat a tired hand.

Once the then-boy signs a piece of pottery the barber has liked the most. The barber shrugs his shoulders, but points at a round bellied vase.

‘That’s the girl who carried her heart around,’ he remarks.

The then-boy looks at him for more.

‘She carried it in her rucksack.’

The then-boy signs, ‘Why?’

Barber Chua smiles. ‘Boy, I don’t even know her name.’