- Vol. 05

- Chapter 01

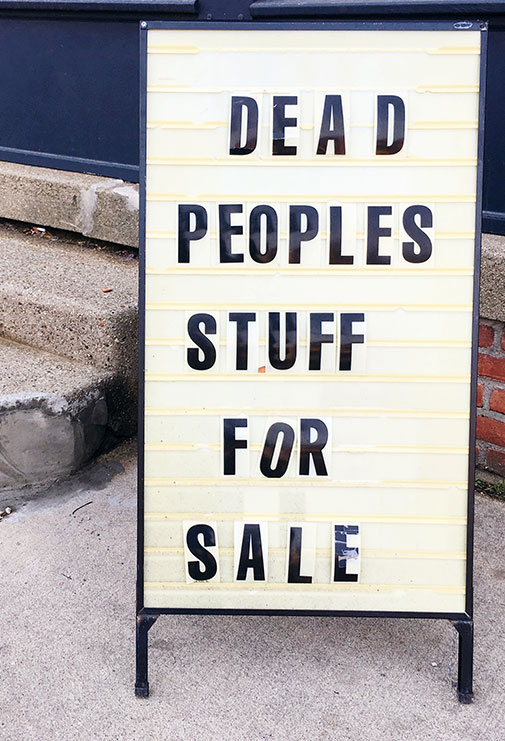

Dead Peoples Stuff For Sale

I don’t think Albert really understood the concept of marketing. If he had he wouldn’t have put those words on the placard outside his shop. I passed it every day on the way to work. The place gave me the shivers, and as for Albert himself, well he couldn’t be far from the grave. Wiry white hair stuck out in all directions. His face was pale and had more track lines on it than Clapham Junction. With a frame thin and unsteady he ambled in and out of the shop, washing his windows and sweeping the step as if that would bring customers in.

Each time I passed my eyes strayed to the piles of clothes and knick-knacks in the window. He hadn’t a clue about window display, how to lure customers in with a tantalising colour co-ordinated hang and drape. And the baskets! There were baskets outside the shop stuffed with socks, ties, tights and underwear.

I wondered about the widows and widowers who gave Albert their dead relative’s clothing. I hoped they washed them beforehand because I couldn’t see Albert putting them through a wash cycle and extra rinse. Many items were so creased and faded the only place for them was in the bin.

The shop overflowed. Clothes spilled out of the door. Thermal vests, shirts, dresses, trousers and jackets. It was a complete mish-mash of fashion. Anything from the thirties to the present day. The paraphernalia of the others’ lives packed shelves and boxes, every corner and every space. Albert certainly didn’t have any competitors in the village, yet the shop suffered the same sadness as his goods. The paint was faded on the façade and the gutters leaked.

In the old days, when he was a young man, Albert had owned a horse and cart and would go from street to street taking away what remained of the dead. He’d just taken over his father’s rag and bone business but he’d changed the criteria.

Dead Peoples Stuff For Sale

I wondered if he got the idea when his father died. Maybe his father’s clothes and personal items were the first to go on sale in his new shop. It was macabre anyway and I couldn’t see that I’d ever set foot in there.But then my father died and I came home one evening several weeks later to discover that my mother had sent a bag of my father’s things to Albert. She hadn’t asked me if I wanted anything, a memento, a keepsake. Angry, and with tears pricking my eyes, I hurried down to Albert’s shop the next morning just as he unlocked the door. Albert followed me around grunting as I asked where my father’s things were. Even the musty aroma didn’t stop me riffling through piles of jeans and baskets of caps and leather wallets. I became desperate as I saw the enormity of the task but I couldn’t stop. There had to be something, anything, left of my father here.