- Vol. 03

- Chapter 02

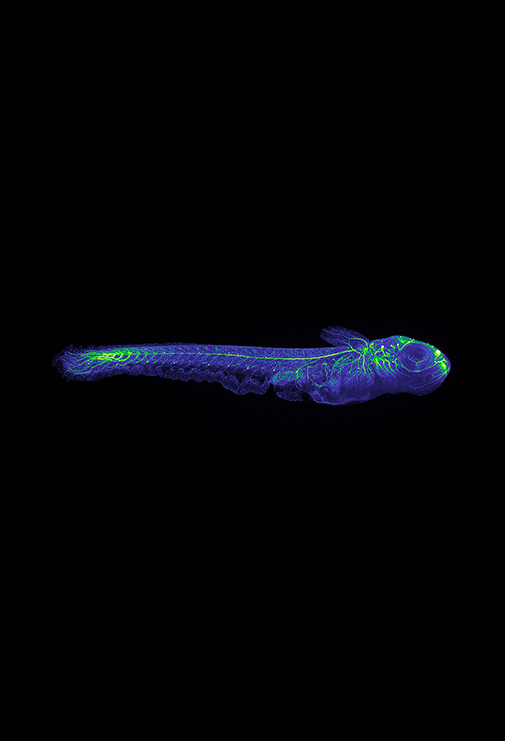

Image by Philipp Keller/Stelzer Group/EMBL

Bones

The doctor came back into the examination room holding a manila folder. He opened his mouth as if to say something, but then stopped. He scratched his head, then he opened the folder.“I don’t know how to ...” he trailed off.

I tried to get under his gaze, to force eye contact, but he was looking too far down.

I thought about pressing him.

But he looked up, he said, “It’s your X-rays. We don’t know how to ... don’t know what they mean.”

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“That’s just it,” he said. He started scratching his head again. “We can’t figure them out. Here. Take a look.”

He turned the folder around and held it out to me so that I could see. There were several X-Rays inside. But I don’t know how to read X-rays, so I looked at them half trying to figure out what I should have been looking for, and half wondering if I would have been able to tell what made good X-rays good, if I had been looking at good X-rays. But even though I couldn’t read X-rays, I could read the doctor’s face enough to guess that I wasn’t looking at good X-rays.

“No?” he said to me after half a minute.

&n“I don’t ...”

“Those are fish X-rays,” he said.

Now I opened my mouth to say something, but I didn’t know what to say, and so I closed it.

“Your bones,” the doctor said after a pause, “they’re fish bones. Here, you can see it clearly along the ribs.” He flipped through the stack of eight-and-a-half-by-elevens and picked out a black-and-white close-up of my torso. “You see, right there,” he ran his index finger along the biggest rib bone on the left rendered in white against the background.

Bones

I looked in his eyes to try to get some sort of a read on what he was thinking.“Are you sure?” I asked.

“I’m positive,” he said, “as positive as I can be, without actually cutting you open and ...”

“Wait, what?” I interrupted.

He closed the folder. “No, that was ... I’m sorry. I just meant, like an exploratory surgery, to confirm the X-rays.” “Do you think that’s necessary?”

“No, I wouldn’t think surgery would be beneficial.” He frowned.

“And so,” I said, “and so what do we do?”

“Well,” he said, “I’d stay away from hot oil.”

I stared at him for a second.

“Some fish bones tend to dissolve in hot oil. Also,” he explained, “fish bones are much pointier than regular bones. I mean, human bones. I mean ... you’re still human. You still look like a human anyway. You should ...” he stopped. “Tell me,” he turned around, “are you a good swimmer?”

“I am a good swimmer,” I said, looking up. “I’m a really good swimmer.”

“Well,” he nodded, “there you go.”

And it’s true. I’m a great swimmer.