Bad Presidents Lie

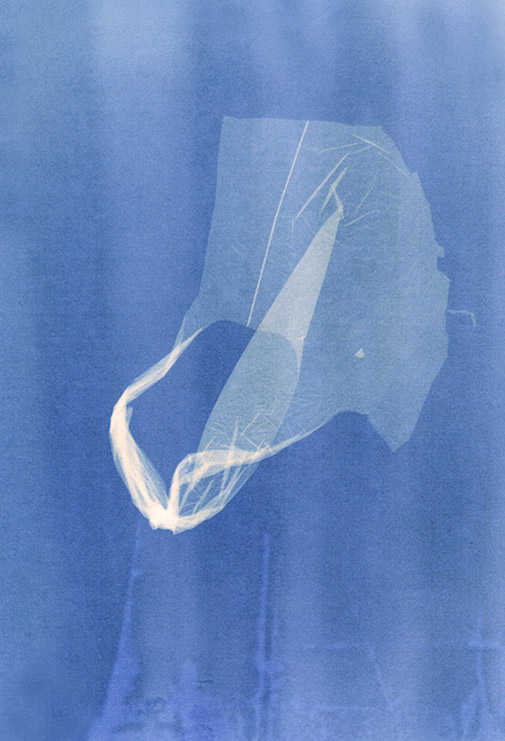

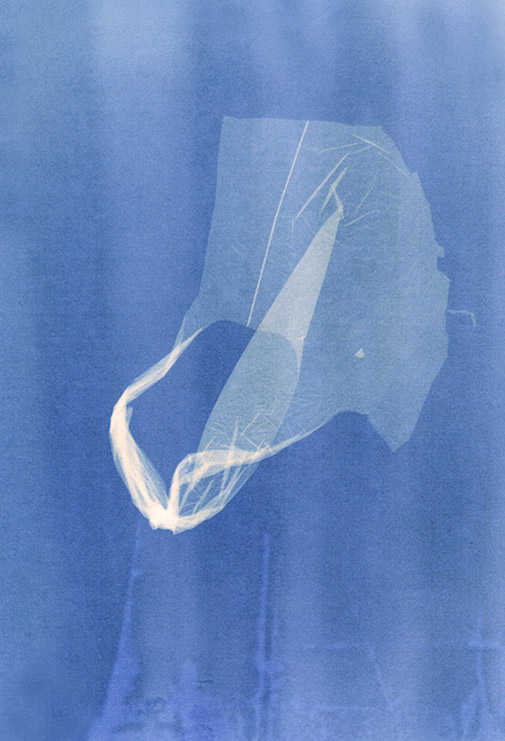

The tissue was left on his cheek, a forgotten ode to the blown flower of his nose, the white of it stark against brown. When he blows, he blows. Whale of a boy, breath a steam engine, each puff a ball hit into left field. When I pump up his blue balloon, he tries to take the air into his mouth, tries so hard to expand himself, inflate up the wall to be as big, as tall as his mom. You are perfect? he asks. I hear it as a statement. My size has always been something to carve away at, no matter how thin. He loves my bare thighs, comes to wrap himself in them. He is perfect. His body has not come from mine. I have trouble, many people say, not staring. They mean that he is that beautiful. It is true. And here on his cheek is the imprint of a cold he caught when the weather warmed, the snowmelt something of a heartbreak for him. He who wants trains in snow permanently; to read of shucking the skirt, to want again to see the caterpillar rescue Thomas. When I peel the tissue from his cheek, what's that he wants to know, there is no trace left of its fleeting kiss. No brittle wing to care not to smear, just paper in my palm to show him. He was once so light, so delicate, so paper thin, his cries so sharp. I folded airplanes for him, the needle-nose, the maniac, the superfly. I made up names and he shot them straight into the floor. Bombers, all of them. When we walk down the icy alley in the early morning, my son always comments on the army vehicles that sit permanently, out cold under blue, torn tarps. They are angry cars, my son says. He has a memory of such vehicles from a time before he was my son.