- Vol. 06

- Chapter 09

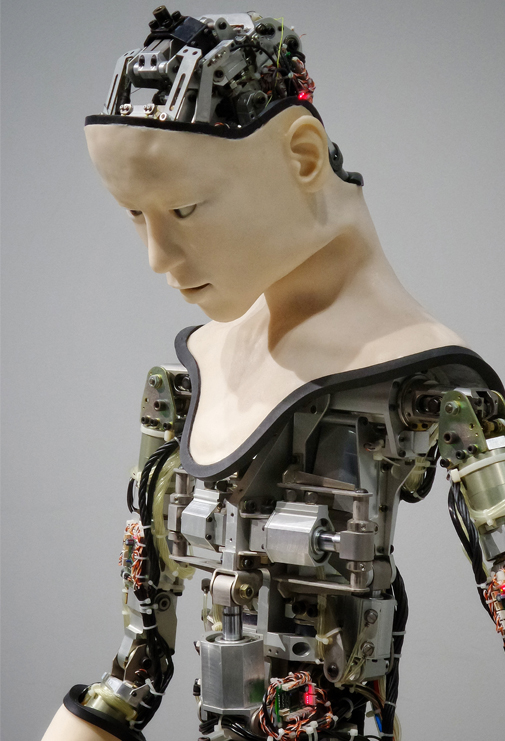

A Poor Substitute

The cogs of my brain are making a racket again. That’s what she always says when I get into this kind of state. “You’re so easy to read,” she complains.

Other people’s cogs don’t get so noisy as mine. I don’t know whether it’s because I’m an old-fashioned model, or because I just feel more than others like me. I really have no idea, because if I have met others like me, I haven’t been able to tell. Maybe it’s partly both. I understand why it upsets her. If I keep emoting so loudly, people might hear; they might realise that I’m not supposed to be here.

She found my inner machinations in the scrap heap. It was like fate, she said. Her daughter was dying, she couldn’t afford the new technology for extending her life. She’s always been pretty handy she said, so using the scraps of me instead wasn’t too much of an effort.

At first, she (my mother, I suppose) was very eager for me to take up where her daughter, (me, I suppose) Gertrude, left off. She showed me pictures of her surrounded by friends, taking part in all sorts of activities. Gertrude was a very popular girl. She also loved to read. I’ve tried reading a few times, but trying to picture anything in my mind puts a real strain on my cogs. As a result, menial tasks have become my pastime; activities where I don’t have to think much, like washing the dishes and mopping the floor. I thought mother would be pleased, but it just made her sad.

“You’re my daughter, not my maid,” she says.

Mother thought maybe it would be different with her friends. I went to play with her—my—best friend Sally, in her house. I tried my hardest to be friendly, to be affable, but I was nervous about playing any games in case the excitement made me noisy. So I started sweeping the floor and dusting the shelves.

A Poor Substitute

I thought she’d find me helpful, but she found me strange, just like mother. I didn’t like the way Sally looked at me, I could tell she didn’t like me. She could hear my sadness then, and her eyes narrowed in suspicion. She whispered something to her mother, then her mother harshly whispered something to my mother, and I haven’t been allowed out of the house since.The way mother looks at me makes me sad too, but I have to try to ignore it, because the racket it creates upsets her. I know that it is a constant reminder that I am not Gertrude. I will never be Gertrude. Despite all her best efforts, although Gertrude’s body remains, the essence of Gertrude is gone. Whatever it is I am, living inside her, leeching off what remains of her, makes a poor substitute.

So I do ignore it; put my sadness elsewhere; let my mind go blank.

I don’t know what to do, so I do nothing.