- Vol. 03

- Chapter 04

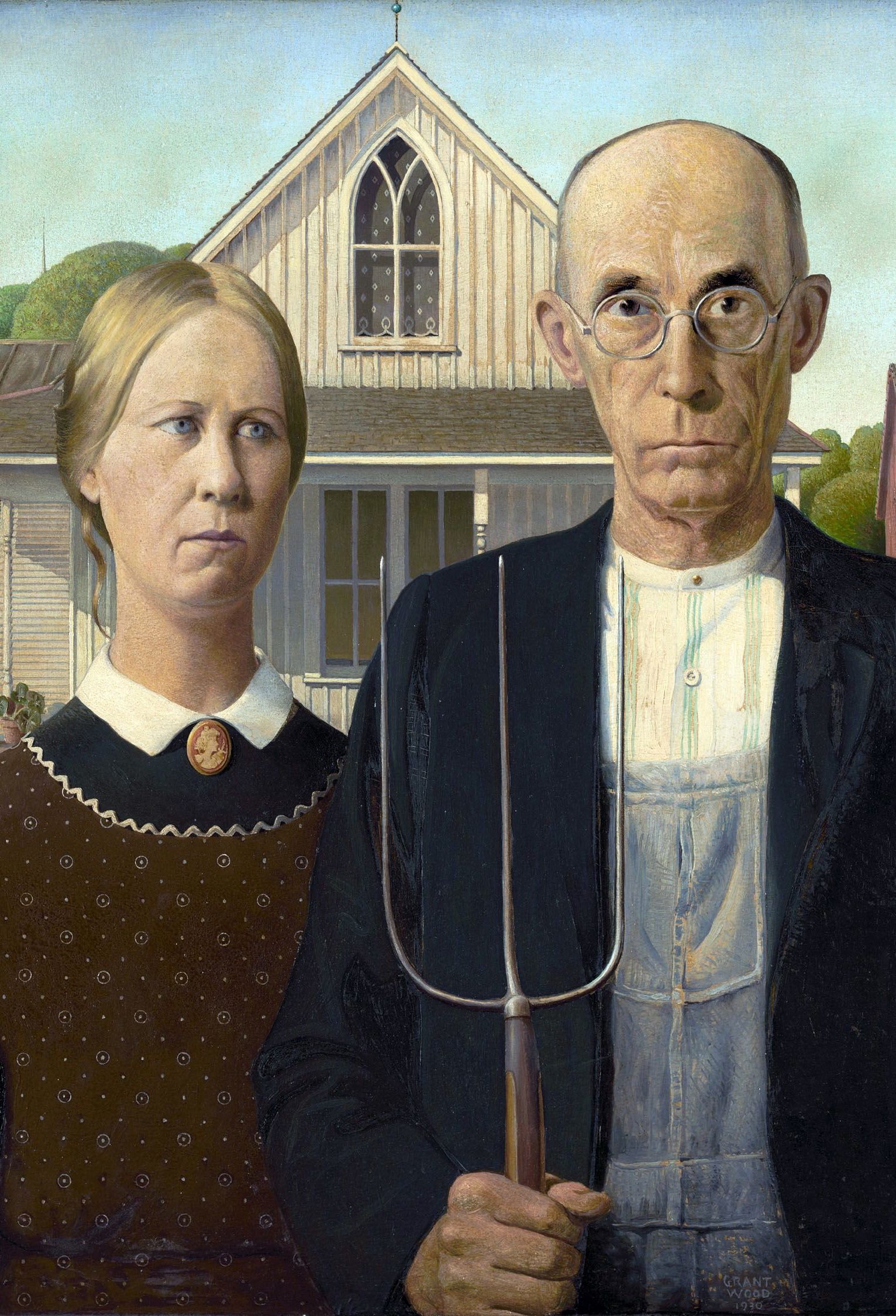

American Gothic Century

He remembers when his mother’s geranium was the homestead’s only grace. She grew it from a slip she brought out from Sweden, when she and his father arrived, way back, just after the war between the states. Its purple blotched leaves, like fading bruises, have survived locust swarms, tornadoes, the plummeting price of wheat.

She will remember a blue and cream Chevy, rounded in front, sharply finned in the rear. It hulks in the dooryard, shrinking the farmhouse further into the background. There’s no room in the picture anymore for the geranium, but it might have disappeared anyway. Lately it hasn’t flowered so much.

He remembers returning home from the fields the day his mother hung the lace curtain in the second story window. From afar, it appeared like snow falling and drifting, fluttering a cool ghost-like welcome.

She will remember how the second story window looks like an eye, aging, growing milky and sightless. It makes her feel as though God is watching her, malevolently or benevolently, she is not sure which. She could hang new curtains, something brighter, more modern, but they would not alter the church-like certainty of the window itself.

He remembers his mother’s cameo brooch that she wore on Sundays, even when the weather was too stormy to go into town for church. She used to let him hold it for a brief moment, while she was still fastening her white collar under her chin. He liked the weight of it in his palm, the chalky topography of the figured head under his thumb.

American Gothic Century

She will remember when she used to think that the cameo’s carved ivory profile was the grandmother she had never met. How she used to envy those whorls of hair, so abundant, so free. And her wings, did her grandmother ascend to heaven through her bedroom window? Now her own hair, a painted beehive, balances above the brooch, leaving no room for mistake.

He remembers his father fashioning a new pitchfork handle after the old one was destroyed in the barn fire. They found the three pronged fork amongst the ashes and the charred roasted flesh of the cow. His father painstakingly and inexplicably fit a piece of walnut he had been saving to the tines and then to a longer pole of ash. The joins have worn together with use, as if they sprang intact from some mutant hybrid life form.

She will remember him brandishing a newspaper, its headlines proclaiming atomic bombs, Communist treachery, Elvis. He’s perpetually angry now. The pitchfork has grown too heavy for him to release his frustrations in useful work. It’s up to her now to keep the barn red, the trees green, the developers at bay. They won’t sell out.