- Vol. 02

- Chapter 07

Quick Human Nature

“Man: good, bad, or indifferent?” is the title of the seminar that finishes playwright Tom Stoppard’s marvelous spoof of academic philosophy, Jumpers. There is plenty of evidence for all three alternatives. In one corner there are the saints and doctors and nurses who risk their lives for others; in the other there are the depraved legions of terrorists and criminals, and in between there are the rest of us: not too bad; could do better, as school reports used to say. There are enough variations in human nature for it to be doubtful whether there is any such thing, as opposed to a virtually infinite pool of different combinations of genes and environments, each capable of throwing up its fair share of oddballs and outriders.

Even when things are what we might call normal, we impose interpretations on each other. We are readier to see people in the light of preconceived ideas than we like to think. It was not only bigots who bought into the “men are from Mars, women are from Venus” myth, just as it is not only bigots who at some deep, inarticulate level, suppose that the French are charming, Scots miserable, Irish talkative, and so forth. Perhaps it is indeed a constant of human nature that we tend to comfort ourselves with wild generalizations.

Many of our theories of things have few, if any consequences. But the problem with wild theories of human nature is that they do have consequences. We can live up to ideals but we can also live down to them. So theories can become self-verifying. If men think that all real men are angry all the time, they may become that much more angry all the time themselves. Women who believe that the way to a man’s heart is to be charmingly ditzy are perhaps more apt to become ditzy than charming.

Quick Human Nature

But the real nightmare of our time is its central figure, home economicus, the rational actor of economic theory: greedy, calculating, selfish, untrusting, untrustworthy, unimaginative and terminally boring. Anyone who is certain that other people are like that runs the risk of beginning to fit the description. And then life goes worse. Humour, art, joy, fly out of the window, but even co-operation becomes difficult or impossible, and the world spirals downhill.

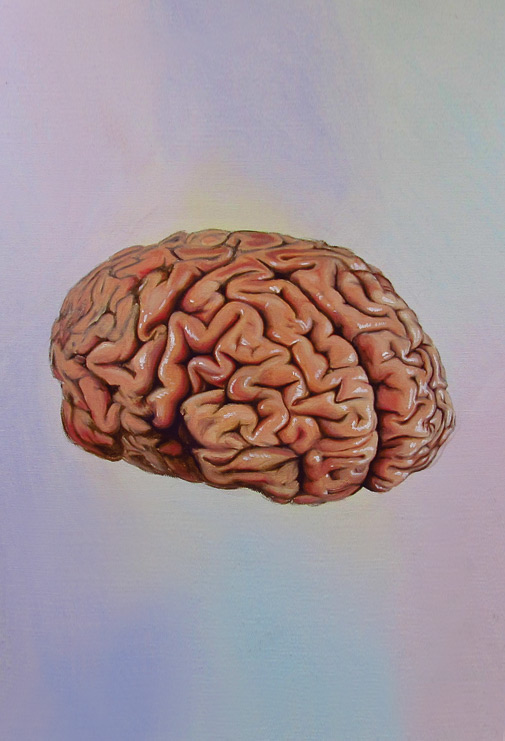

The philosophers who explored human nature, from Plato to Hume, to Hegel to Wittgenstein, used observation and history to help them. Today it is more likely to be white coats and fMRI scanners. An advantage of the older approach is that it takes people as they act on the world’s stage, rather than when they are stuck immobile in a highly artificial environment imagining how they might behave on the world’s stage, probably inaccurately.