- Vol. 02

- Chapter 07

Mama

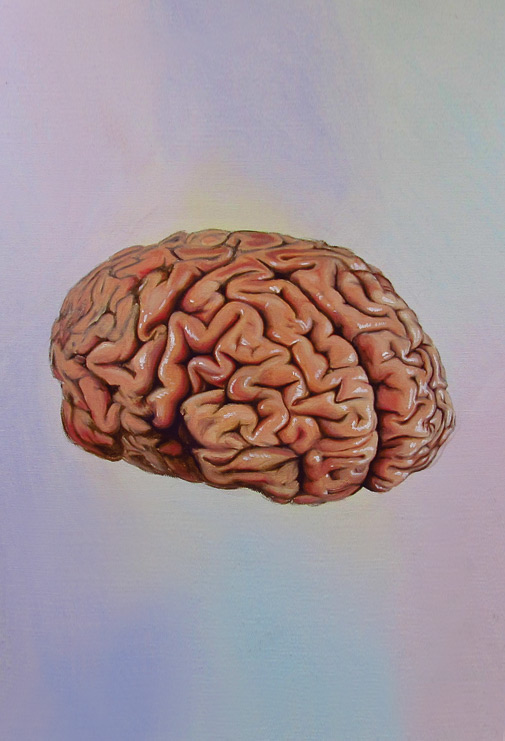

Mama was dead.

Well, brain dead, at least.

That’s what her doctor said. I wasn’t too fond of him—all harsh angles and dark eyebrows and bulging eyes—but the nurses that checked on her every hour or so would pat my head and smile, so I liked them, I suppose.

Human beings aren’t supposed to move that fast. That’s what crazy, old Mr. Riley told me one day a few weeks after the accident. I was walking home—Pa made me walk, said he wouldn’t dare get in the car, no siree, not when everything in Clinton was well in walking distance—home from school, my hands shoved in my front pockets, kicking a pine cone down the sidewalk, when Riley stopped me for a chat.

You can imagine my surprise. Mr. Riley never spoke to anyone. I’d hardly ever seen him, too, save for the few times he came to church—Christmas and Easter—and that one time Chris and me wondered what would happen if we set off bottle rockets in Mr. Riley’s front yard. In fact, until that very day, the only words I’d heard him speak were, “Get off my fuckin’ lawn!”

“What’d you say to me, you crazy old man?” I’d hollered at him.

“Our bodies aren’t made to go that fast. Drivin’,” he’d said. He’d flicked his cigarette at me. I’d taken a step back. “Won’t be surprised if she never wakes up. No I will not.”

Not too sure if I really said anything to him after that. My eyes started burning something awful, and the next thing I remember, I was at home, tears running hot and fast down my face. I’d been crying a lot those days.

Mama

Once the doctors told Pa that Mama was brain dead, he started drinking an awful lot. I’d come home from school, sweat rolling down my back from the hot September sun, and the whole place would smell like bourbon. One time—the only time there was even a drop left—I put the bottle to my lips to understand what it was like to be an adult. I’ll never forget the taste.

“Now, son, you understand what this means,” he’d say to me when we found out.

“Sure,” I’d said. “It means she’s in a coma.” That was back when my arm was in the brace from the accident, and Pa still had bruises and cuts on his cheek from the windshield breaking when Mama’s body launched through it.

“Son, it means she ain’t wakin’ up,” he’d told me.

“She will,” I'd said to him. “She will, just you see.”

Four days later we were lowering her into the ground, cuz Pa decided it was “unfair” to leave her hanging on like that. I heard the words “pulled the plug” so much in the months afterward, that it became a sort of mantra in my life.

Pulled the plug. Pulled the plug. Pulled the plug.

Like she was a lamp, or somethin’.