- Vol. 02

- Chapter 08

Afterward

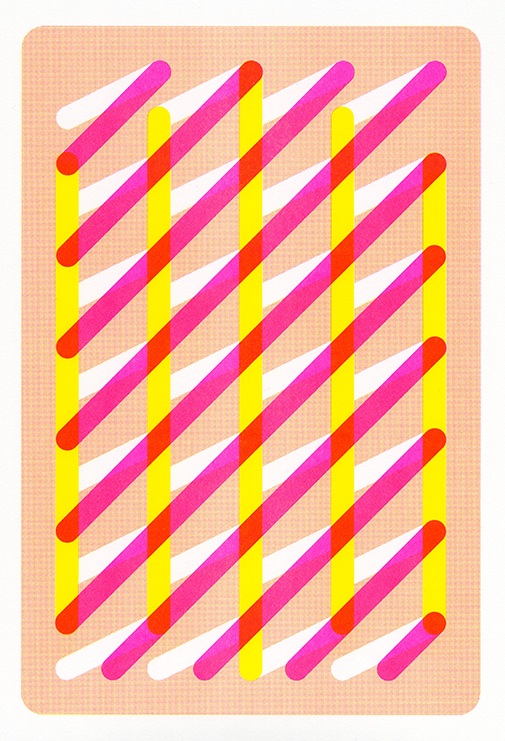

Afterward, she said all she could remember was the lights—pinks and yellows, soft and warm. Brilliant, swirling, crisscrossing, and, dare she say, breathing lights.

“I swear, it’s like they were alive.”

They say acid will do that to you.

Even for weeks afterward, she saw the lights, dancing at the peripherals of her sight, flashing across her eyelids when she closed her eyes for the night, sometimes even swimming in front of my face, she said.

“I wish I could’ve seen them,” I told her.

“Do it with us next time.”

Who knew how long next time could take, though, because she got bad again shortly afterward. She stopped seeing the lights dancing, and so she began locking herself in her room, drinking from dark bottles and smoking something that filled the whole apartment with a putrid stench. The smell was the worst part, because no matter how badly I wanted to lie next to her in that bed and wrap my arms around her shaking frame—knowing fully that I would feel her shoulder blades digging into my chest like blunt arrows—I couldn’t, because the smell of her smoke made my stomach twist, and I began working doubles to pay the rent.

“Baby,” I’d say, tip-toeing into the room, knowing she couldn’t hear me even if I stomped. “I gotta go into the restaurant now.”

“Hmmm?”

“I love you, Ash,” I’d tell her.

For a long time, she didn’t say it back.

Afterward

She always got better, though, after awhile. She’d spend her few weeks locked away in our bedroom, but afterward she’d emerge, bleary-eyed and starving, raving about all the things she wanted to do that night, all the people she wanted to see. She’d kiss me hard and fast on the mouth and say, “Please tell me you don’t have to work.” During those moments, she was a firework show.

While she scarfed down whatever food we had in the kitchen—usually not much, since I ate at the restaurant, and she didn’t eat when she got bad—I’d call into work, making up some excuse if I talked to a manager, telling the truth if I’d talk to the chef.

“Is she better?” the chef would always ask. He knew I never got sick. He knew we couldn’t afford it.

“For now,” I’d say.

“All right, Beth. I’ll make something up for you.”

This time, when I hung up the phone and went back into the kitchen, she was dipping her finger into a jar of peanut butter.

“So,” she said, eyes glittering, “what should we do?”

I went to her then, wrapping my arms around her. “I’m so glad you’re back,” I told her, because that’s what I was supposed to say. Her skin was hot, blazing.

“Oh!” she exclaimed suddenly. “We should do it. You should see the lights.”

I told her I couldn’t tonight. I didn’t want to see the lights. Because I didn’t want to miss them when they were gone.